Natural Enemies: Growing Views on Conservation

Page 1 of 3

American attitudes toward wilderness and environmental politics are continually transforming. From Western colonization until the early 1800s, society viewed the wilderness as something dangerous; an enemy that needed to be mastered, dominated, and contained; an infinite resource created for man’s consumption.1 Even those that felt awestruck by the majestic beauty of the landscape also felt a moral duty to clear the land, impose order on it, and make it economically productive2— a view that is evident in James Fennimore Cooper’s 1826 novel The Last of the Mohicans3. It was not until the mid-19th century and the rise of Transcendentalism that this view would begin to change and the groundwork for conservationism was born.

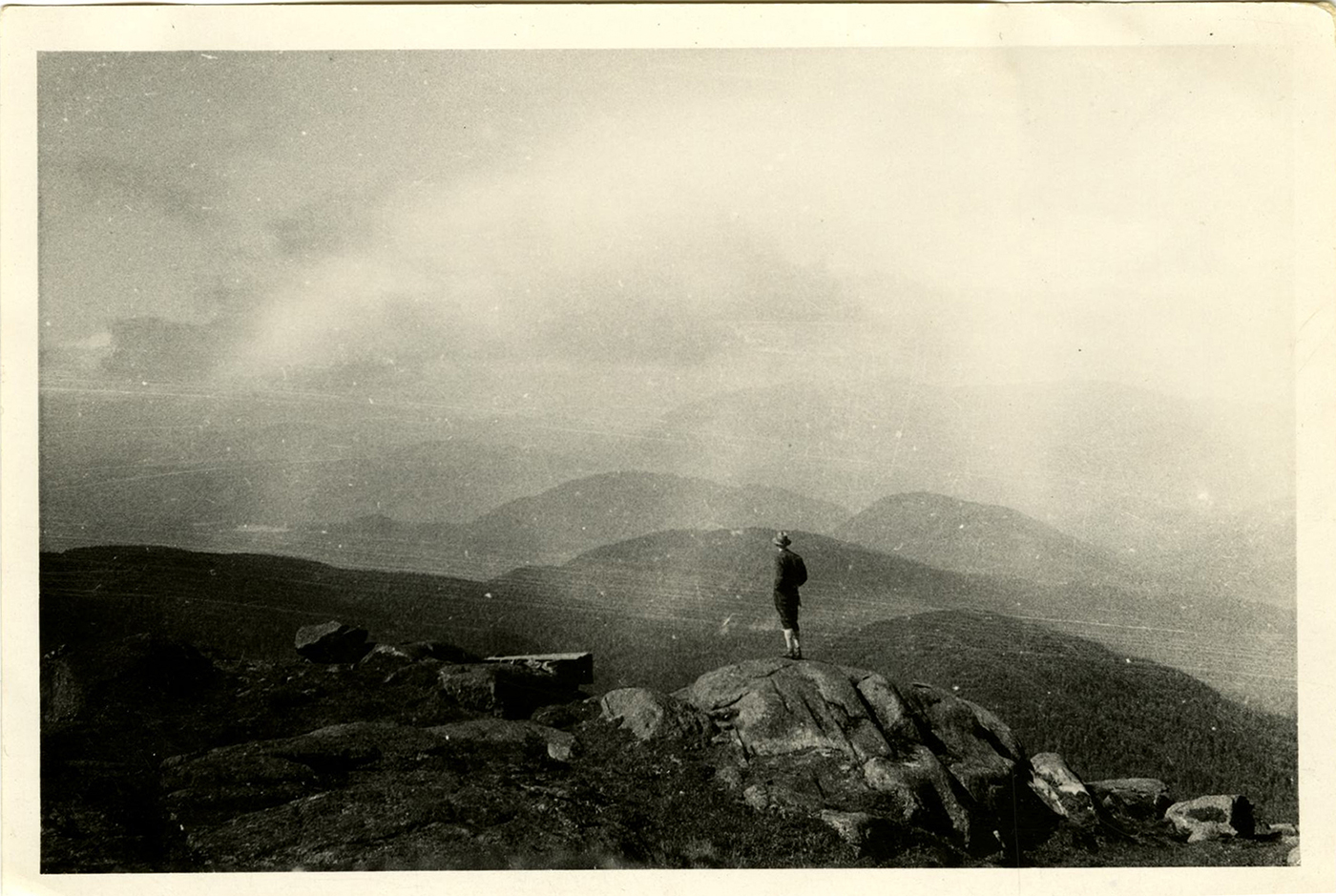

In 1836, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) published Nature, in which he argued that there was a spiritual reality higher than the physical that could be reached through the study of the natural world. Nature was a perfect medium to understand the divine because “nature is not fixed but fluid; to a pure spirit, nature is everything”.4 Transcendentalism prompted a new American perspective on the wilderness in which nature held intrinsic value, and had the ability to act as an antidote to the corrupting influence of society. This new view of nature led to the development of camping as a recreational activity—a chance to escape the oppressive influence of civilization and know one’s “true self”.

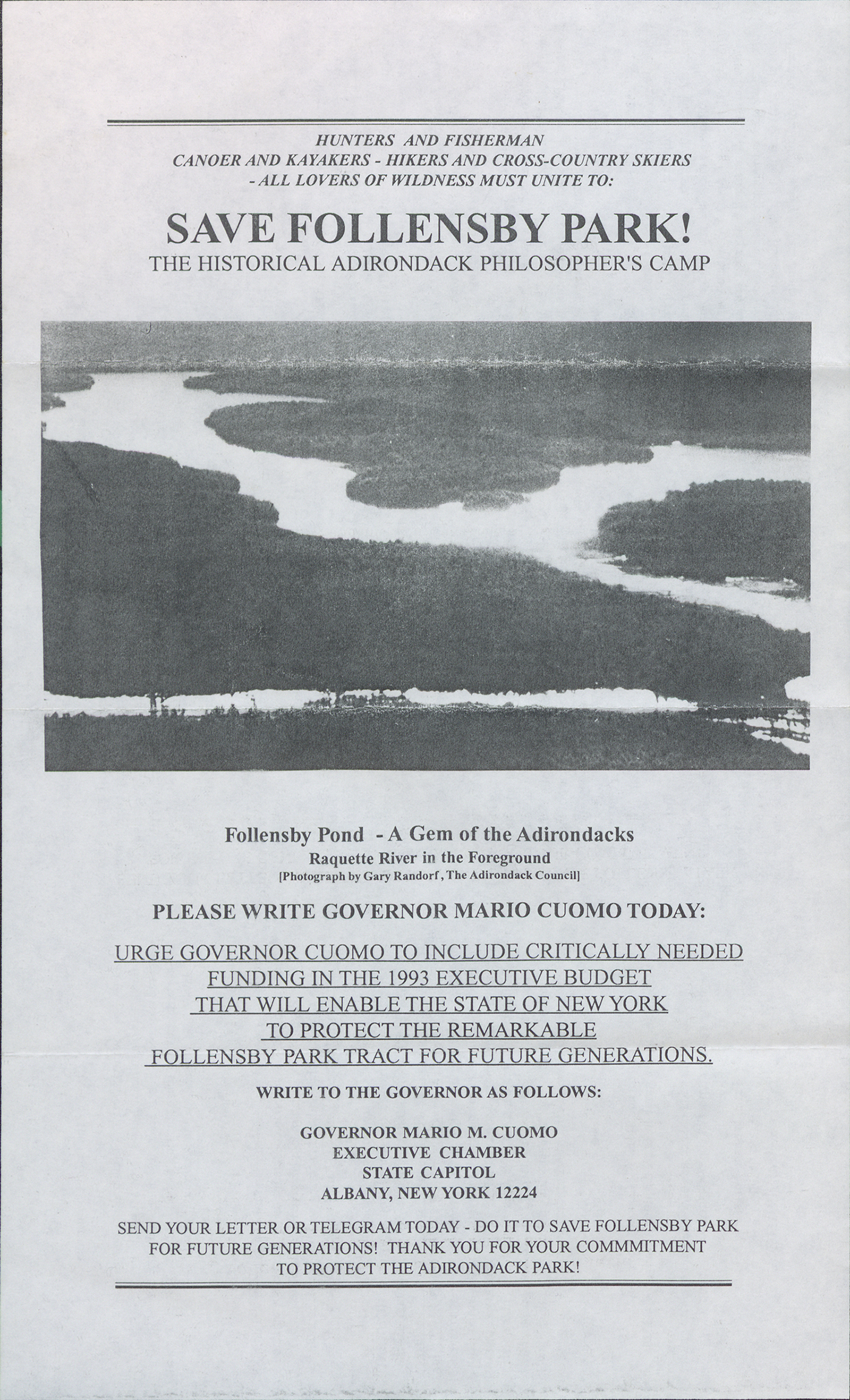

During the summer of 1858, Emerson, William James Stillman (Union College class of 1848), and eight other philosophers and artists traveled to Follensby Pond in the Adirondacks and built a rough camp out of natural materials. They stayed for one month, connecting to the spiritual power and beauty of the landscape. It was a transformative experience. Inspired by their surroundings, Emerson wrote the poem “The Adirondacs,” and Stillman painted “The Philosophers’ Camp in the Adirondacks”. The wide-reaching impact of these works elevated the prominence of the region. Soon, summering in the remote New York mountains was en vogue and a who’s who of Americans began visiting the region. Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and Carnegies built ‘great camps’ (large, expansive estates) in the region. Over the following century, the popularity of vacationing in the Adirondacks would only grow.

In the footsteps of Emerson, two figures further shaped American thought on wilderness during the late 19th century: Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) and John Burroughs (1837-1921). Thoreau, the father of American nature writing,5 famously wrote in his 1851 essay “Walking” that “in Wildness is the preservation of the World”.6 Thoreau believed that nature was our mother, imbued with incandescent perfection. Thus “man’s improvements, so called, as the building of houses and the cutting down of the forest… simply deform the landscape, and make it more and more tame and cheap”.7 Thoreau was an early proponent of both camping and canoeing, although he preferred “partially-cultivated country” to true wilderness. His essays on forestry and speeches at agricultural colleges sparked a dialogue on regulatory conservation.8

1 Nash, Roderick. Wilderness and the American Mind. (Yale University Press) 1982: 27

2 Boag, Peter. Environment and Experience: Settlement Culture in Nineteenth-century Oregon. (Berkeley: University of California Press), 1992: 98

3 See: Peprnik, Michal. “The Place of the Other: the Dark Forest.” In “Nature’s Nation” Revisited: American Concepts of Nature from Winder to Ecological Crisis, edited by Hans Bak and Walter W. Holbling, 339-346. Amsterdam: VU University Press, 2003.

4 Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Nature. (East Aurora, NY: Roycrofters), 1905: 89

5 Parini, Jay. The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2004. 495

6 Thoreau, Henry David. Nature and Walking. (Beacon Press) 95

7 Ibid. 80

8 Jurretta Jordan Heckscher, ed. (3 May 2002). “Selected Events in the Development of the American Conservation Movement: 1847–1871”. The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850–1920. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.