John Apperson’s Early Battles

Page 1 of 6

A lake is a landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is Earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.

-Henry David Thoreau, Walden1

Lake George, at the southeast base of the Adirondack Mountains, was sparsely populated by family farmsteads and subsistence loggers until the Erie Canal connected the region to the commercial world in 1825. Taking advantage of the new, easy and cheap transportation, factories and lumber mills began to arise in the mid-19th to 20th century. Thomas Cole’s illustrations for James Fennimore Cooper’s 1826 bestselling novel The Last of the Mohicans popularized the area. The crowds of tourists who traveled north on the Canal’s steamboats soon swarmed the shores of the lake. A booming tourism industry emerged, and the wealthy began purchasing the lakeside real estate that had been ignored by the local farmers because of its limited agricultural value.

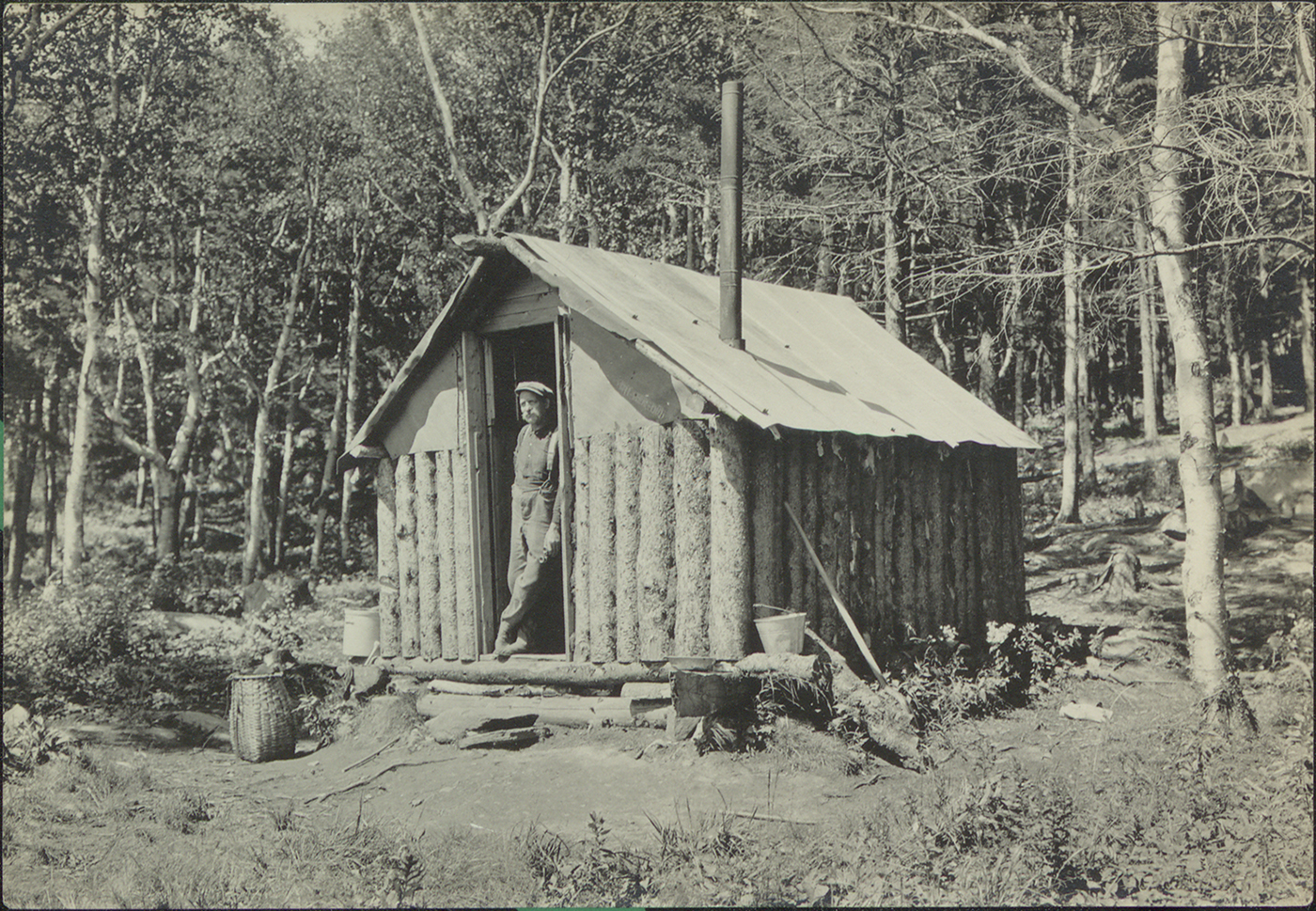

The lake’s shorelines rapidly developed to house hotels, sanitariums, summer camps and personal ‘camps’. Unique to this region, an ‘Adirondack camp’ is a “permanent summer home where the fortunate owners assemble for several weeks each year and live in perfect comfort and even luxury, tho [sic] in the heart of the woods, with no very near neighbors, no roads and no danger of intrusion”.2 The grandest camps, known as ‘great camps,’ formed Millionaires’ Row near Bolton Landing and Diamond Point on the shoreline. Although they were referred to as ‘cottages,’ they were in fact palatial homes, as large as 20,000 square feet and situated on large tracts of landscaped property with luxurious amenities such as private tennis courts. The juxtaposition between the region’s older, rural, hardscrabble, agricultural inhabitants and the new influx of urban upper- and middle-class summer residents radically changed the region’s demographic climate. Both the tourism and logging industries demanded a seasonal workforce, pulling locals from their farms and flooding the woods with migrant camps.

Prior to the establishment of the Forest Preserve in 1885, it was legal to reside on state land in the Adirondacks. This practice allowed residents to avoid paying property taxes on their homes. These ‘squatters’ camps spanned the socioeconomic spectrum. Some of them were composed of migrant workers’ shanties and lean-tos. On the other hand, many of the Lake George squatters were from among the wealthiest residents of Gilded Age New York: Collis Huntington, Andrew Carnegie, John Boyd Thacher, William d’Alton Mann3, and Robert J. Collier among many others4. These wealthy families erected palatial summer homes on “the most desirable… sites”5 of publicly owned land. It was an open secret that these families, although they had no valid deed to the land, had a “right” to be there by virtue of “knowing the right politician”.6 Thirty years after the 1885 law, more than 600 squatters’ camps illegally remained in the Adirondacks.7

1 Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. (London: Dent) 1910: 441

2 Dix, William Frederick. “Summer Life in Luxurious Adirondack Camps.” The Independent 55 (Jul. 2, 1903): 1556-1562.

3 “State Orders Rich Squatters Off Preserves.” New-York Tribune, July 31, 1915.

4 “Rich and Poor Squatters Must Give Up Land in Adirondacks.” The Evening News (San Jose, CA), July 31, 1915.

5 “Adirondack Squatters and Camp Owners Clash.” The New York Times, November 15, 1903.

6 Fowler, Barnett. “State Conservation Leader Buried” Times Union (Albany, New York), February 10, 1963.

7 “Rich and Poor Squatters Must Give Up Land in Adirondacks.” The Evening News (San Jose, CA), July 31, 1915.