This Land is Your Land: The Birth of ‘Forever Wild’

Page 1 of 4

Initially, the timber industry in the Adirondacks grew slowly due to the difficulty of transporting felled trees out of the remote region. Significant logging and lumbering began in the Adirondacks around 1813, and by 1850, New York had surpassed Maine to become the largest producer of lumber in the United States.1 Industrial growth and urban expansion fueled the demand for lumber. As America expanded westward, prospectors sought lumber from the old-growth forests of the Adirondacks. American railroad expansion increased the rate of logging. Only two ties “as a rule could be cut from a single tree”.2 As a result, it is estimated that during the railroad expansion boom (1810-1890) 30 million to 60 million trees were consumed per year.3

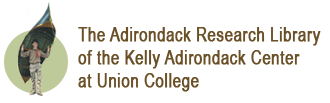

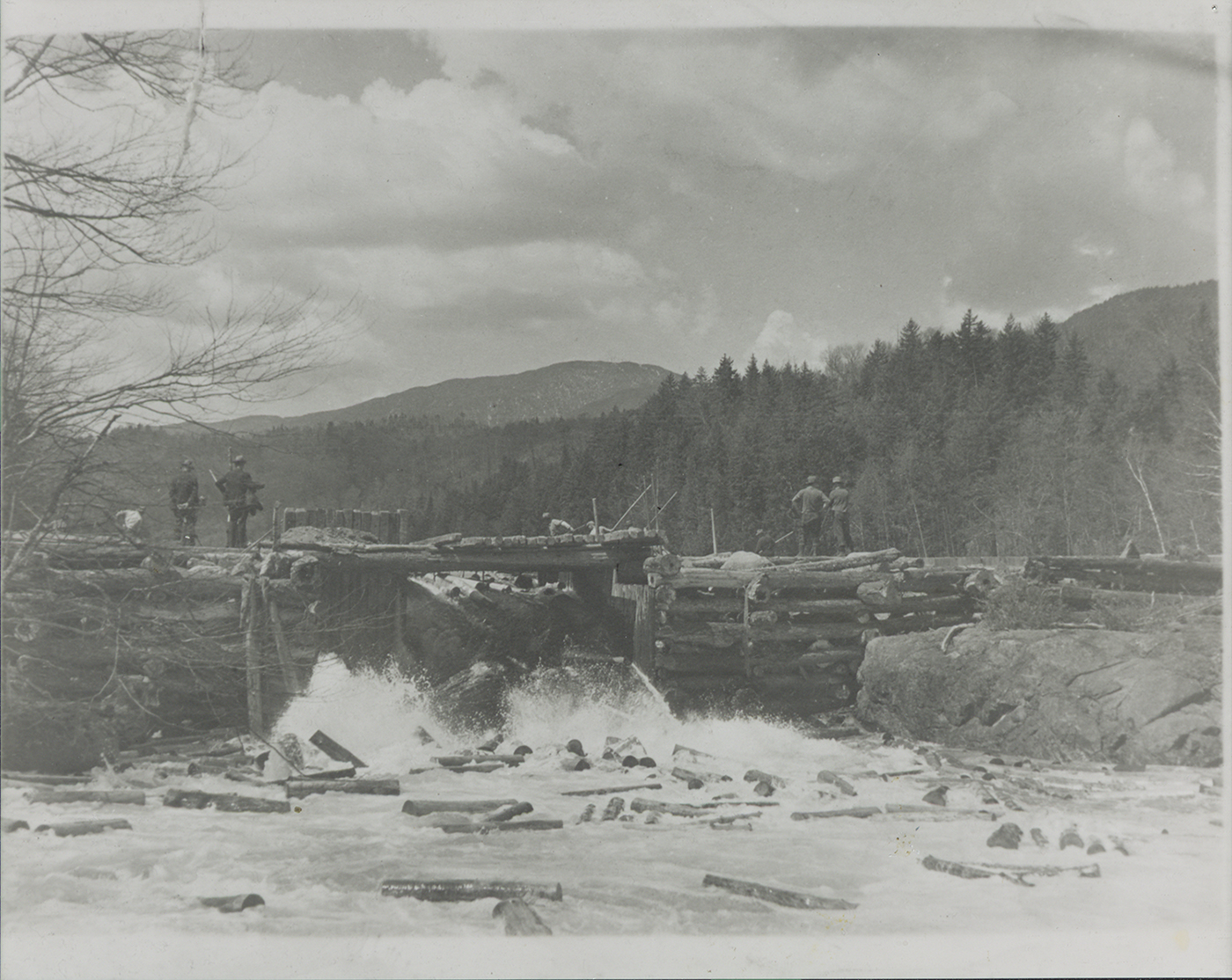

Before the expansion of timbering in the Adirondacks, lumbermen transported trees from the forests to mills by thatching logs into rafts and floating them down waterways. Teams of mules and men would haul the log-rafts overland around obstacles, waterfalls, or cascades.4 The log-raft method, however, was not successful in the mountainous terrain of the Adirondacks, so a new technique was developed: the “loose-log drive”. Large groups of un-thatched logs were “driven” (floated) down rivers and streams.5 Tree felling took place close to rivers and streams in the fall and early winter. Lumbermen would then strip the trees of their bark and limbs before leaving everything on the forest floor until returning in the early spring. This cycle allowed the logs to cure for a season while also utilizing the high water levels and quick currents of the spring melt for their transportation. Softwood trees, such as pine, hemlock, and spruce, rather than hardwoods, such as maple and birch, quickly became the focus of the loggers as the greater buoyancy of the softwood trees led to easier transport.6 The techniques developed in the Adirondacks influenced logging nationwide.

The rampant loose-log drives in the Adirondack region distressed riverfront property owners. The unsecured logs damaged delicate shorelines and monopolized water traffic. In order to protect the timber industry from the complaints of property owners, the New York State Legislature declared many portions of rivers in the Adirondacks “public highways” between 1806 and 1846. This designation gave loggers full authority to use these waterways for lumber transportation.7 By 1885 logging had removed between “fifteen to thirty percent of the forest cover”8 of the 6.1 million-acre region. This equates to between 915,000 and 1,830,000 acres of denuded forest. “No area in America has had a more miserable story [than the Adirondacks] of ruthless squandering of natural resources and of carelessness based on the supposition that the stock of… trees, was infinite”.9

1 Paul Schneider, The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997): 202.

2 Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park: A Political History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978): 95.

3 Ibid..

4 Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park: A Political History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978): 7-8.

5 Paul Schneider, The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997): 210.

6 Ibid. 202.

7 Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park: A Political History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978): 8. See also: Paul Schneider, The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997): 214.

8 Barbara McMartin. The Great Forest of the Adirondacks (Utica, New York: North Country Books, 1994): 68.

9 William Chapman White, Adirondack Country (Virginia: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1954): 26.