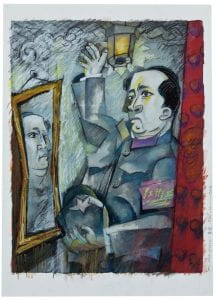

As an exhibition designer, my theme is to focus on one aspect of Cai Guo-Qiang’s works, which is the use of gunpowder as a medium for his art. Gunpowder has been used as a weapon of destruction for centuries, but Cai has transformed it into a medium for creation, a medium that has allowed him to create awe-inspiring works of art.

The use of gunpowder as a medium for art is not only unique but also significant in understanding art in 20th century China. It reflects the cultural and political context in which Cai grew up and how it has influenced his artistic vision. Cai was born in Quanzhou, China, and grew up during the Cultural Revolution, a period of great social and political upheaval in China. He was also trained in traditional Chinese painting, which heavily influenced his art.

Cai’s use of gunpowder as a medium is a reflection of his desire to break free from  the constraints of traditional Chinese painting and to experiment with new mediums and forms. It is a reflection of

the constraints of traditional Chinese painting and to experiment with new mediums and forms. It is a reflection of

his interest in exploring the relationship between art, nature, and the environment. Cai’s gunpowder works are not just about the process of creation but also about the process of destruction and the cyclical nature of life.

In my exhibition design, I will showcase a selection of Cai’s gunpowder works, including his famous “Gunpowder Drawing” series. I will also include a video installation that shows the process of creating these works, highlighting the physicality and danger involved in the creation of gunpowder art.

By focusing on Cai’s use of gunpowder as a medium for his art, my exhibition design aims to contribute to our understanding of art in 20th century China. It reflects the cultural and political context in which Cai grew up and how it has influenced his artistic vision. It also highlights the importance of experimentation and breaking free from traditional forms in art. Finally, it encourages the audience to consider the relationship between art, nature, and the environment, and how art can be a reflection of our interactions with the world around us.

Work cited:

Neuendorf, Henri. “Watch Cai Guo-Qiang’s Explosive Performance.” Artnet News, 16 Apr. 2016, news.artnet.com/art-world/cai-guo-qiang-gunpoweder-performance-475250. Accessed 15 May 2023.

ROFFINO, SARA . “Cai Guo-Qiang Burns up the Art Scene This Fall.” Galerie, 18 Sept. 2017, galeriemagazine.com/snapshot-cai-guo-qiang/. Accessed 15 May 2023.