Chen Danqing first left the comfort of the Shanghai metropolis at the ripe age of 17 as a result of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution policy to expose the revolutionary youth to the struggle and toil of the Chinese countryside. This was a formative and integral part of Chen’s youth as he, along with tens of millions of other metropolitan youth, was forced into an unrecognizable and uncomfortable new environment. Upon the closure of the Cultural Revolution in the late ‘70s, Chen cultivated a passion for Native Soil Art, influenced by French realist Jean-Francois Millet. He sought to employ Native Soil styles to depict the harsh realities of the lives of China’s ethnic minorities, particularly those living in the Tibetan Autonomous Region.

Chen has published numerous paintings on the lives and traditions of the nomadic peoples living in the Tibetan region; their ways of living, cultural nuances, traditional beliefs and practices, occupations, and more. Thus, this exhibition will focus on the meaning behind Chen’s into Tibetan culture and the objective of Chen’s portrayal of Tibetan culture through his unique Native Soil techniques. Typical in Native Soil Art, realism is stressed in the portrayal of personal expressions, landscapes, and objects portrayed in the image, often an earthy, almost ominous coloring. Native Soil techniques, fully opposed to the techniques employed during the Cultural Revolution, help popularize a burgeoning realist faction in Chinese art circles in the 1970s and ‘80s. These groups sought to identify the struggles and successes of the Chinese people through harsh, realist portrayals rather than glorified, optimistic socialist-realist styles. Not only does Chen seek to demarcate the normalcy and uniqueness of the average Tibetan’s life, but he also aims to depict the tangible nature of Tibet and its peoples, often considered an exotic and faraway region to most living on China’s east coast.

In Chinese mainstream media, those living in Tibet are often subjected to labels such as anti-Beijing, subversive peoples who seek to liberate themselves from the rule of the CCP. However, employing techniques typical of Native Soil Art, Chen depicts Tibetan people for who they really are; he highlights their longstanding cultural and religious practices, the intimacy of family and interpersonal relationships, and most importantly, the negligible differences between them and the majority Han population.

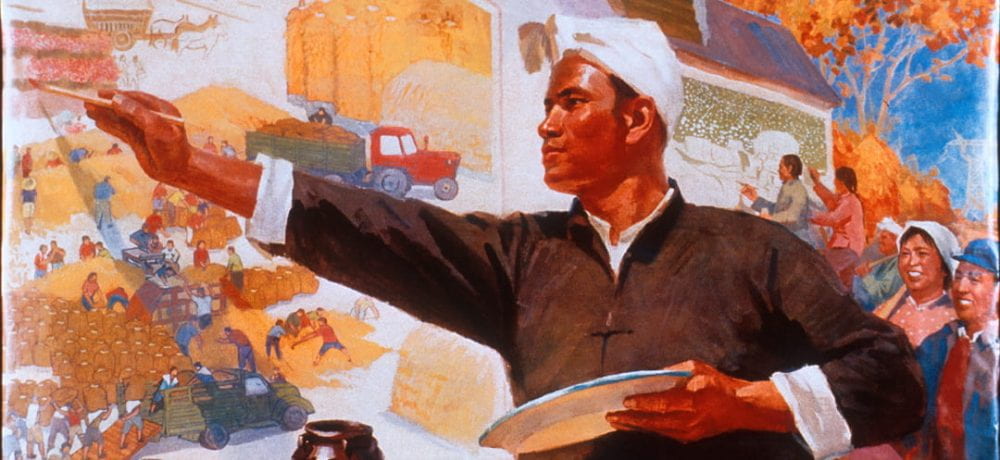

Chen Danqing (b.1953), Harvest Fields Flooded by Tears, 1976. Oil on canvas, 120 x 200 cm. Image source: artnet.com

Depicting the toil and struggle of the Tibetan peoples in their primarily agricultural and nomadic lifestyles, Chen delineates a clear message: Those living in Tibet are remarkably similar to those living in Wuhan, Beijing, and Shanghai. While their garb, physical appearances, and spiritual beliefs may differ from their Han compatriots, their identity as Chinese and life experiences indeed draws similarities and connections with the rest of the Greater China population.

Citations:

Galimberti, Jacopo, Noemi de Haro García, and Victoria H. F. Scott. Art, Global Maoism and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Manchester University Press, 2019. muse.jhu.edu/book/71777.

Kao, Arthur Mu-sen. The Dormant Volcano of Art in China: New Art Policy and Art Movement. Journal of Developing Societies, 74-90, 1994. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1307823101?accountid=14637.