For my final exhibition I will examine the modernist woodcut movement in China and its unique relationship with communist politics.

The woodcut movement in China was revived by Lu Xun to produce a more socially-aware art medium for the people. He combined the traditional Chinese print form with Western techniques to introduce a new style for the woodcut print that criticized the social and political circumstances in China. Lu Xun and many other left-wing scholars started to believe that the woodcut print was the best medium to portray the social and political upheaval in China. Not only was it cheap and easy to mass produce, but the raw aesthetics helped promote powerful messages. The characteristics of linearity, sharp contrast of black and white, and Western realism presented an influential design that had a persuasive impact on its audience. Lu Xun started to use this medium of art as an educational tool, where he could communicate his ideas and reshape what people thought of China. This became a vigorous weapon of the people that Lu Xun used to reveal the harsh realities of imperialism and feudalism to promote socialist modernity.

The woodcut print became a revolutionary new medium of art that diverged from Chinese traditionalism and promoted modernity. The woodcut print had soon developed activist traditions that provided the common people of China a voice. In Lu Xun’s final years of his life he became a patron, where he promoted this socially-aware art form to help better the Chinese society. However, after Lu Xun’s death in 1936 and subsequent years of the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) the woodcut print began to experience radical new developments.

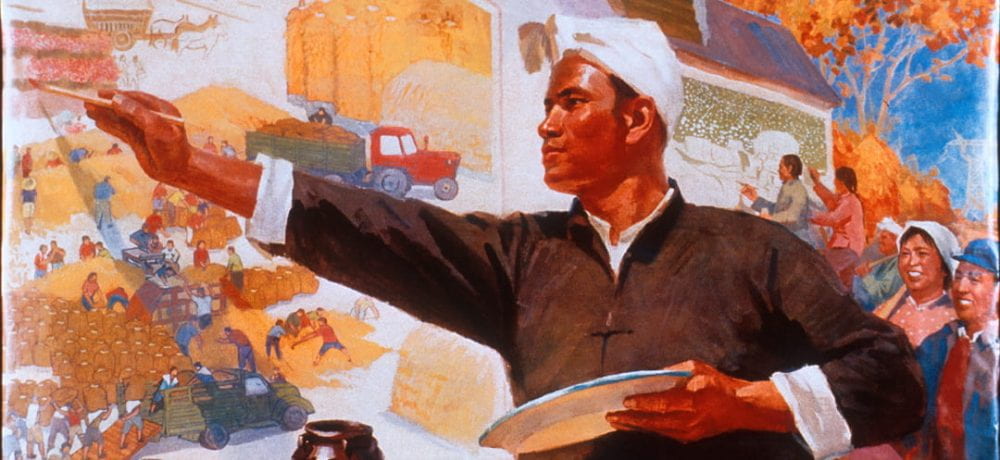

Although Lu Xun was never an official member of the Communist Party, his emphasis on the exploitation of peasants and the working class coincided with the political aims of the Communist party (CCP). As a result the Communist party (CCP) adopted the woodcut print and repurposed it to be used as a weapon against their political enemies. This transformed the art of the people into communist propaganda. In Mao’s Yan’an Talks (1942), the leader of the Communist party redefined the role of art in China. The modernist woodcut movement was now strictly used for political purposes only. Chinese woodcuts became associated with the Communist party, which consisted of two types: nationalistic– which attacked the imperialists and GMD, or socialistic– which praised the CCP (Hung 1997, p.35). After Lu Xun’s death, the woodcut print was controlled by the Communist party, which restricted artistic freedom and reshaped its purpose to align with communist politics.

Through several works the audience can see the transition of woodcuts before and after it was adopted by the Communist party…

Li Hua, Roar, China! woodcut, 1938.

Li Hua, Raging Tide I: Struggle, woodcut, 1947.

Li Hua, Arise, woodcut, 1947.

Yang, Yanbin, Mao Zedong, woodcut, 1945.

Li Qun, To Live in Abundance, woodcut, 1944.

Gu Yuan, Protect Our People’s Troops, woodcut, 1944.

Citations:

Lin, Pei-Yin. “Print, Profit, and Perception : Ideas, Information and Knowledge in Chinese Societies, 1895-1949,” edited by Weipin Tsai, BRILL, 2014.

Hung, Chang-Tai. “Two Images of Socialism: Woodcuts in Chinese Communist Politics.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 39, no. 1 (1997): 34-60.