For my research project I aim to focus on the cultural impacts that propaganda posters create and sustain in both the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union. I plan to focus primarily on the ‘cults’ associated with each state, conducting a comparative analysis between the two to demonstrate the vast similarities, while simultaneously noting the differences between the two. As such, my primary focus will be on the span of time when Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin were the respective leaders of these nation-states. Within this particular short essay I aim to focus primarily on China, as if I were to discuss both China and the Soviet Union in depth I would likely spill over the word limit by a large margin.

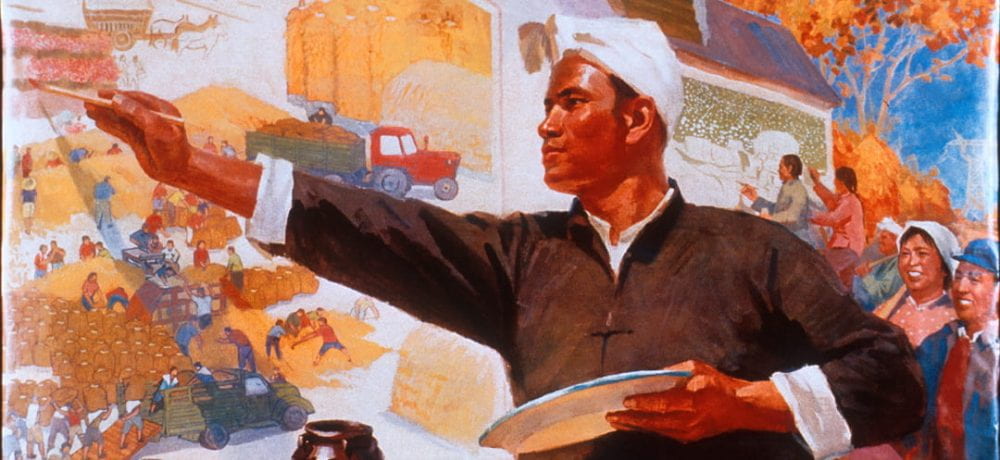

China, during Mao’s reign as the Chairman of the People’s Republic, suffered significant economic and social catastrophes. As a result, the communist party needed ways in which to appease the public, or at least pacify them during these calamities. One of the solutions Mao and his party devised was an intense political campaign focused around the idea of class struggle. A particular quote from Mao which helps to demonstrate this was “‘never forget class struggle’” (Young, 40). By focusing upon this class struggle, Mao and his cohorts were able to effectively shift malice for their failing state away from themselves, and redirect it towards capitalists (Young, 43-44). By pumping propaganda posters out that stressed the idea of class struggle and the glorification of the proletariat, citizens were less likely to question the continuous state of revolution that was harming their state and themselves (in particular, the Cultural Revolution).

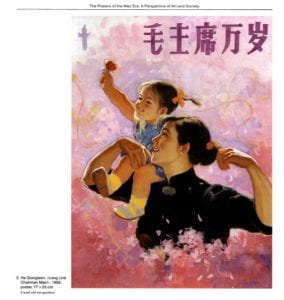

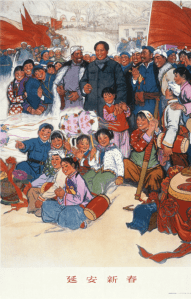

Propaganda in China also played a major role in sustaining Mao’s cult of personality (a cult of personality being a regime that uses a variety of techniques to create an idealized image of their leader, allowing for facile manipulation of the public). By using propaganda to facilitate this cult (and other social engineering techniques that I will discuss in greater detail in my final project), Mao was elevated to an almost god-like status. This obviously was problematic for a plethora of reasons, but with the most prevalent being the refusal of anyone to question his authority, even on matters that others possess far superior knowledge (Buruma, “Cult of Mao Zedong”). This in turn helped to facilitate the various economic and social catastrophes during Mao’s rule. Unsurprisingly, Mao actually adopted much of his political ideologies from Stalin, whom he met with numerous times. As such, it is rather important to examine the Soviet Union when analyzing the People’s Republic, as they are quite similar (yet also different) in many regards.

Within my final project I aim to include: a poster by Dadao Ribendiguozhuy that stresses the “evil” nature of capitalists, a poster by Ha Qiongwen that was widely criticized by the Communist Party for not depicting Chairman Mao and instead depicted a proletariat woman and child, and a poster by Naum Karpovsky that demonstrates the cult of personality in the Soviet Union. Obviously I need more political posters to reach the requirement of five, however as of right now I aim to gather more information regarding my thesis/theme before I determine which posters I will include (in the chance I discover some information I wish to represent along with a visual).

Works Cited

Young, Graham. “Mao Zedong and the Class Struggle in Socialist Society.” The Australian Journal of

Chinese Affairs, no. 16, 1986, pp. 41–80.

Buruma, Ian. “Cult of Mao Zedong.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 7 Mar. 2001,

www.theguardian.com/world/2001/mar/07/china.features11.