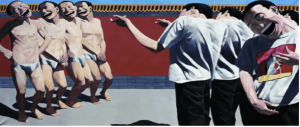

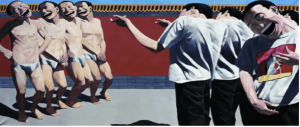

Yue Minjun’s oil painting “Execution” broadcasts its powerful message through content, colors, composition, and subjects. Yue has instituted an inventive and unique style for self-portraiture work. Specifically, he is best known for his oil portraits that depict his own laughing figure in different iconic moments in history.

Yue Minjun (b. 1962), Execution, 1995. Oil on canvas, 59 x 118 in. Image source: Forbes.com.

Regarding the colors in this painting, the red wall is certainly noteworthy. My first impression of the painting was the red colored wall, which instantly spurred the thought of death. Moreover, the red color is ironic because the victims who were about to be executed would soon have blood all over them that would match the color of the wall. The red color is also contradictory to the statement above, as the color is traditionally associated with happiness and propitiousness, creating a rigid dichotomy of interpretation.

Specifically, the event in China that ignited Yue to paint this piece was the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest, which resulted in a massacre by the government that killed thousands of innocent Chinese citizens, including students. This protest was largely a demonstration for a democratic movement in the country. During this period in China, many citizens were skeptical and critical of Deng Xiaoping, then the leader of the country. Many Chinese felt that the Deng administration was restricting their independence, including freedom of speech and freedom of the press. The protests began on April 15th, 1989 and ended June 4th, 1989, when the Chinese government declared martial law. Many of the student protestors began a hunger-strike to outline the level of social and political injustice present in the country. The declaration of martial law in this instance enabled the government to partake in immeasurable and unnecessary violence, by equipping troops with assault rifles and tanks. What started as a vehicle to convey political expression, quickly escalated into a bloodshed event that further suppressed Chinese citizens’ civil rights (Wikipedia).

There are several key features in this painting. First and foremost, the painting illustrates the political dysfunction in China during this period. Specifically, the victims (on the left-hand side) have been rounded up by Chinese armed forces, being punished for their protests of the Chinese government. As mentioned above, many protestors in this movement decided to participate in hunger-strikes. The victims on the left-side appear to be malnourished, with their bones almost popping out of their chests. Shifting focus to the subjects on the right-side, these men are troops in the Chinese military. Interestingly, the firing squad holds no guns, instead, with one troop cocking his hands like he is in possession of an imaginary gun. The invisible gun is enigmatic, in the way that it is difficult to precisely analyze what Yue was aiming to symbolize. Anthony Daniels, the author of the article “Yue Minjun’s haunting laughter,” notes that this paradox creates a potential charade, as all participants are laughing in a deeply sad situation. Furthermore, Daniels states that “the charade is about as amusing as would be that of an extermination camp;…and the fact that people are constrained to laugh at the imaginary reenactment of executions of themselves (if that is what the picture depicts) suggests likewise that the dictatorship, at least that over minds, has not yet passed” (Daniels 2013).

The most important feature of this painting is that all the subjects have a big, over-exaggerated smile on their faces, bringing comical dimension to the slaughter being shown in the painting. According to Yue, “at first you think [the person] is happy, but when you look more carefully, there’s something else there…a smile doesn’t necessarily mean happiness; it could be something else” (Bernstein 2007). Evidently, the act of smiling in this painting, especially by the victims, portrays the powerlessness that they possessed at this moment. Perhaps what Yue is also trying to display is the way that the helplessness of the victims caused their tears to convert to laughter.

Yue’s painting resembles almost identical components to that of legendary Spanish painter Francisco Goya’s 1814 painting May 3 in Madrid or “The executions.” In both paintings, suppression and political controversy are an apparent theme. In respect to Goya, he based his work on the Spanish resistance of Napoleon’s army in 1808, where innocent Spaniards were murdered by the French (Museo Del Prado).

Francisco Goya (b. 1776) May 3 in Madrid or “The executions,” 1814. Oil on canvas, 8′ 10″ x 11′ 5.” Image source: museodelprado.es. Museo Del Prado, Madrid, Spain, room 064.

Work cited

“1989 Tiananmen Square Protests.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, April 16, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1989_Tiananmen_Square_protests.

Bernstein, Richard. “An Artist’s Famous Smile: What Lies Behind It?” New York Times, November 13, 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/13/arts/design/13smil.html.

Daniels, Anthony. “Yue Minjun’s haunting laughter.” New Criterion, Vol. 31, Issue 10 (June 2013) (accessed April 16, 2020) https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A334486089/LitRC?u=nysl_ca_unionc&sid=LitRC&xid=4292b9f5

“The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid, or ‘The Executions.’” Colección – Museo Nacional del Prado. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/obra-de-arte/el-3-de-mayo-en-madrid-o-los-fusilamientos/5e177409-2993-4240-97fb-847a02c6496c.