Wild at Heart: The Education of Paul Schaefer

Page 4 of 5

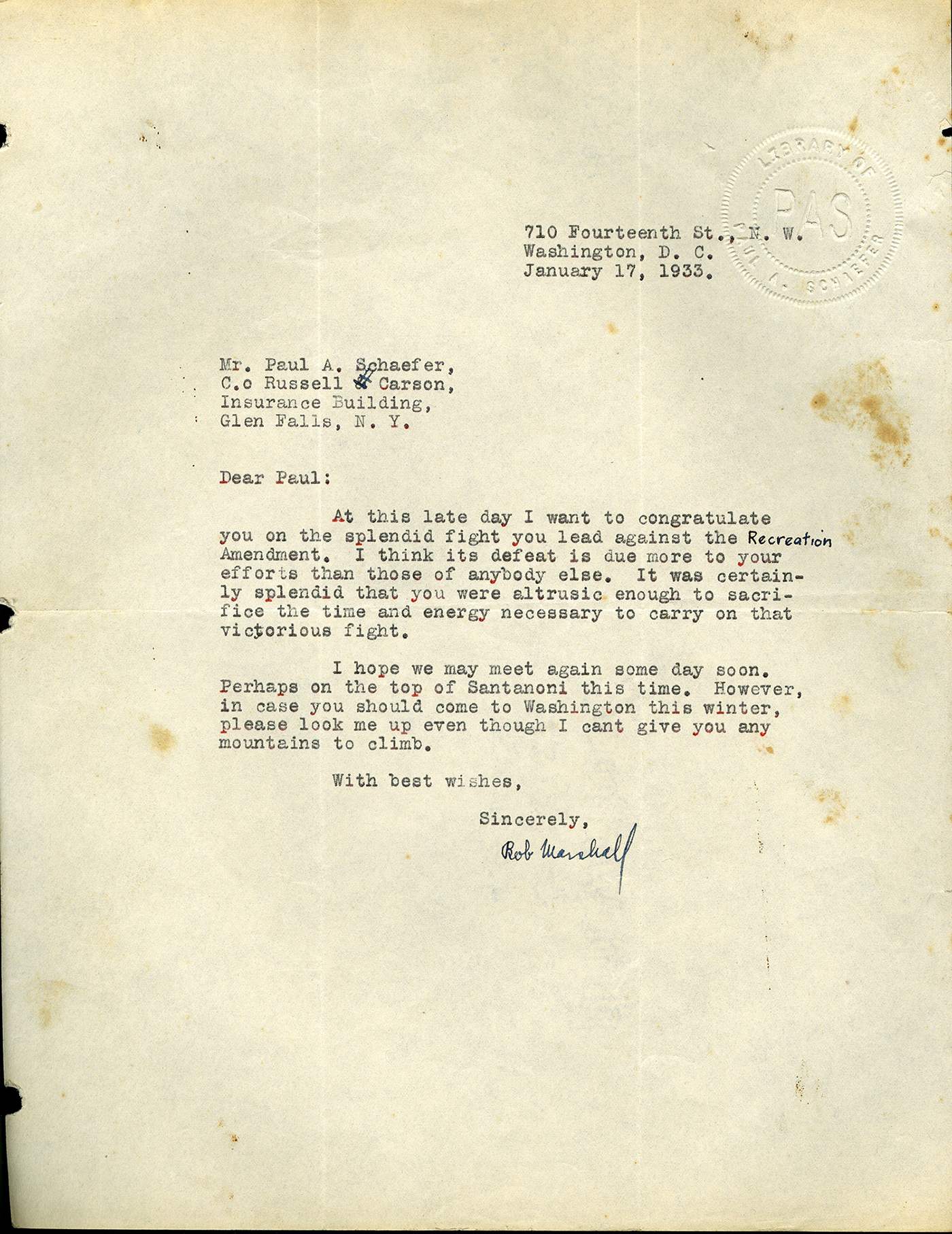

Throughout the fight against these amendments, Apperson became increasingly impressed with Schaefer’s innate skills. Schaefer had a natural gift for bringing people together, which when combined with his enthusiasm, patience, and rhetorical skills, turned many influential conservationists against the CCA. In 1931, Schaefer published an essay, “The Adirondack Lean*to”, with compelling criticisms against the amendment. Schaefer argued that the construction of resort or furnished cabins would “open avenues of chaos”1 that would soon “become commercialized and exploited for selfish interest”2. Additionally, Schaefer contended that these types of “recreational facilities” would rob people of the ability to “meet Nature on even terms”3. After months of lengthy correspondence, Schaefer brought hundreds of conservationists to the fight when he was able to shift Russell Carson, the president of the Adirondack Mountain Club, against the CCA.

By 1932, more than 150 sportsmen’s groups and conservation organizations from around the Northeast had been united under Apperson and Schaefer against the CCA.4 In the months leading up to the 1932 general election, members of Apperson and Schaefer’s coalition published articles, delivered public speeches, and mailed thousands of pamphlets to New Yorkers throughout the state.5 Their argument was simple: The CCA was unnecessary, as hundreds of hotels, boarding houses, dance halls, and ski lodges already existed on private lands within the Park. Additionally, both primitive camping spots and camping spots with car access and modern facilities already existed within the park.6 On November 8, the people of New York voted down the Closed Cabin Amendment by a 2:1 margin.7

By 1932, Apperson had adopted Schaefer as his conservation protégé. Schaefer watched Apperson:

pursu[e] his devotion methodically, like the engineer he was, disdaining sentimentalism and vague rhetoric for hard facts. Before he wrote a stinging letter to a state official or presented a statement at a public hearing he spent days going over the site of controversy, grasping details of law and topography that often put ‘experts’ to rout.8

Apperson encouraged Schaefer’s emergence into the spotlight of the conservation debate. In the coming years, Apperson emboldened Schaefer’s growing confidence and advised him on gathering data to firmly ground his arguments. However, it was not until the impending conflict over truck trails that Schaefer truly found his voice.

1 Paul Schaefer. The Adirondack Lean*To, 1931.

2 Correspondence, Paul Schaefer to Samuel H. Ordway, December 7, 1931.

3 Paul Schaefer. The Adirondack Lean*To, 1931.

4 Opposition to the amendment was supported by Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Henry Morgenthau, Herbert H. Lehman, Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, Professor Ralph S. Hosmer of Cornell University, Dean Hugh R. Baker, Professor Nelson R. Brown of Syracuse University, Ellwood R. Rabenold, NY Chapter of the Society of American Foresters, The Mohawk Valley Towns Association, the New York Chapter of the Appalachian Mountain Club, the New York Division of the Izaak Walton League of America, Mr. WIlliam B Greekly, the Schenectady County Conservation Council, The Camp Fire Club of America, over 3,000 farmers, The Women’s City Club of New York, The Adirondack Mountain Reserve, the Mohawk Valley Hiking Club, the Garden Club of America, and others. See: Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, “State Wide Opposition to the ‘Recreation Amendment.” President’s Report, June 9, 1932 .

5 Paul Schaefer to Mr. Carson, July 22, 1932.

6 “Mountain Club Hits Proposal,” The Schenectady Gazette, January 28, 1932.

7 Vote was on November 8, 1932. 393,542 YES, 1,326,599 NO, 2,749,602 Blank! See: “Vote of the State of New York on Amendment Number 1: use of forest Preserve for Recreation Purposes.”

8 Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park: A Political History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978): 173.