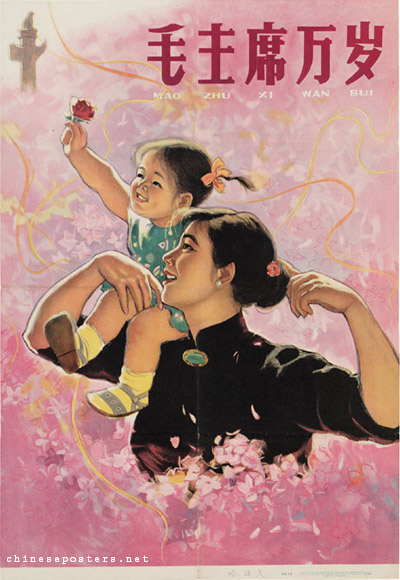

Generally speaking, it is difficult to pinpoint a specific artist that created propaganda posters in China during this time because many artists were not given credit for their work. Art was seen as a public service, and propaganda posters were government messages that were mass produced and highly profitable, so it seemed as though these pieces of art (called xuanchuanhua) were just generally coming out of the government instead of an individual. Contests were held at a nationwide level to select certain propaganda prints for the year.The mass production of these removed the personal and individuality of the artist out of the final product. So, instead of identifying a specific artist for these propaganda posters, it will be easier to decipher this unique form of art through a theme, such as the representation of women during this era through these posters. The purpose of these xuanchuanhua were to relate and speak to the largest portion of society: the peasants, the workers, and the middle class. Women made up a large portion of those classes, and were encouraged to help the nation in their efforts just as much as men. In this particular example, “Long Live Chairman Mao”, is showcasing a celebration of the 1959 May Day Parade. This artist (one of few that was famous for specifically creating propaganda posters), Ha Qiongwen, needed to create an optimistic print in the wake of the “disastrous” failures of the Great Leap Forward, and so chose bright colors and a woman carrying a joyful child on her shoulder. This is the first of many examples where we see propaganda posters using a woman’s to uplift the community and being a pillar of support for the country.

Ha Qiongwen (b. 1925), Long Live Chairman Mao, 1959, gouache on paper printed as poster, 110 × 80 cm, shanghai people’s fine Arts publishing house

Citation:

Andrews, Julia Frances., and Kuiyi Shen, The Art of Modern China, California: University of California Press, 2012