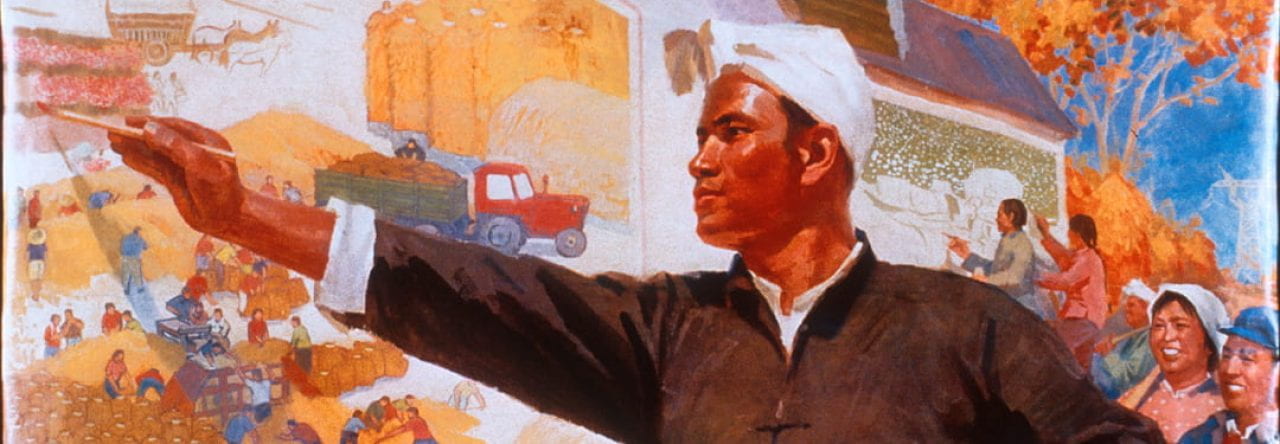

“With the sun in your heart, what is there to fear? Dare to sacrifice your youth with the people.”, Artist unknown, gouache on paper, Shanghai, 1976

For many years in the Communist Party’s reign over China, these posters were a way of connecting the government with its people. This propaganda-producing business usually churned out millions of posters annually, and had become so efficient at creating political posters that it would take less than a day to draft, print, and distribute new material for the masses to consume (Andrews, 2012).The purpose of these posters were to encourage the majority of society- the working class, peasants, farmers, and soldiers- to unite together as equals under one country. In this unity and idyllic society, everyone is treated as equals, which includes men and women. Mao Zedong explicitly states that “women can do the same as men”, and supports them in every way as long as it benefits the party (Evans, 1999). Women are allowed to dress, work, and have the same political power as men. This stance has given women the freedom to appear in artwork in the same company as men and give society examples of what their role is in this “new” China.

This poster below features a line of mostly young women with their arms linked to form a chain. They are forming a human dam against massive tides of water, withstanding the crashing waves with determined expressions. The caption below the poster reads: “With the sun in your heart, what is there to fear? Dare to sacrifice your youth with the people.”, and underneath that caption is another, saying “learn from the eleven educated youths of Shanghai’s Huangshan TeaTree Factory, who feared neither bitterness nor death.” (Evans, 1999). It is a gouache on paper, and is most likely a local propaganda poster. The fact that the image features mainly women goes to show how seriously women’s roles in Communist society were taken. They can bear the same hardships as men with equal resilience and determination. The main woman in the foreground of the work is clutching the “little red book”, a book of Mao Zedong’s sayings that the Red Guard often carried around. She is the only one in this poster whose face is showing fear. Though she appears as a “weak link” who allows the rushing water to pass by the human chain, she is still holding on and has a tight grip on the little red book, thereby solidifying her willingness to stand strong by her government and their beliefs.