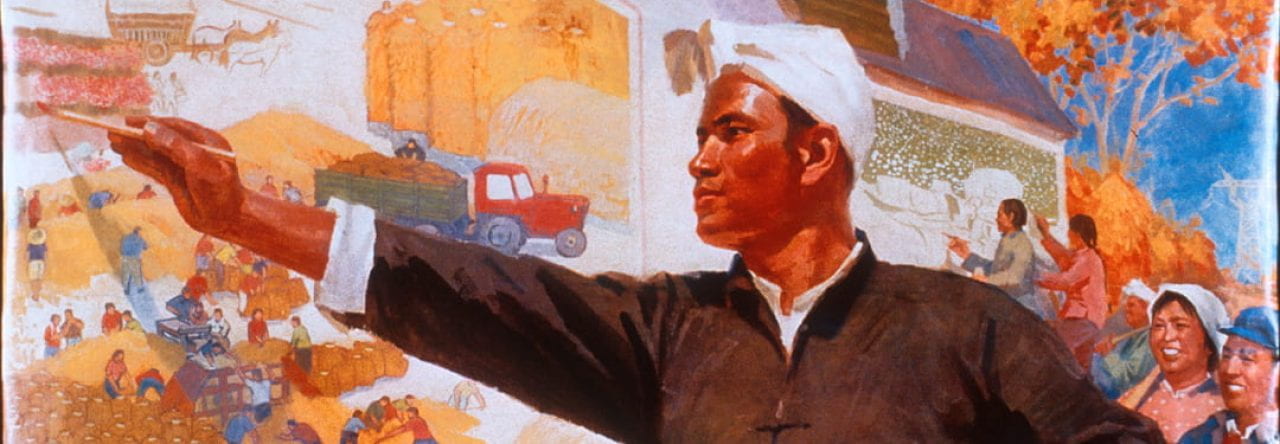

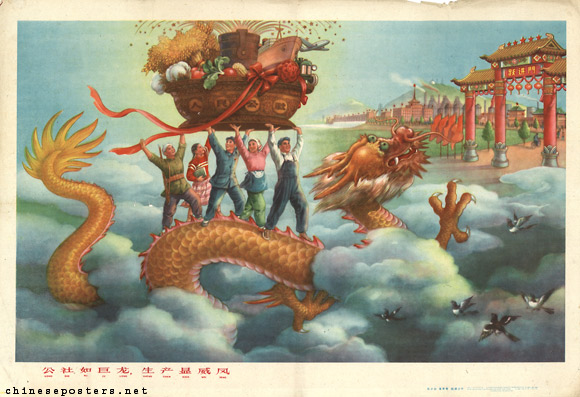

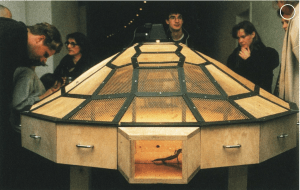

During the 1980’s Huang YongPing co-founded an artist group which became known as the Xiamen Dada group. The group was considered one of the more radical avant-garde groups emerging from China at the time for their unique styles, and their cultural critiques. Xiamen Dada became part of contemporary Chinese art history in 1986 when their works were on display at the Exhibition of Modern Art which was held in Xiamen People’s Art Museum. Their works gathered mass attention, and critiques when the group decided to publicly burn their works at the end of the exhibition in defiance of the cultural, and political revolutions going on in China at the time. Primarily the group was protesting the leader of the People’s Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping, and his desire to return China to a socialist government with more Chinese characteristics (Doryun, 2015). This act of arson sent shock waves through the art community as people were puzzled as to why an artist would destroy something beautiful that they created themselves. Huang, and other members of the Xiamen Dada group chanted “Without destroying art, life will never be peaceful.” (Dawei, 2022). This idea of finding peace within destruction coinciding with China reopening its doors to the west after its painful cultural revolution goes to show how even in the most trying of times there is still hope for a better future. Continuing further with this idea, it is evident through the progression of Huang’s works throughout his career that he is able to use forms of destruction to create new ideas and styles. In essence works like Xiamen Dada, Reptile, and Theater of the World served as pedestals for Huang allowing him to mix different styles from different cultures, specifically traditional Chinese culture and modern western culture that was beginning to flood China. For my exhibition I would like to incorporate fire somehow (maybe a fire pit around campus) and begin a sort of maze throughout campus showing Huang’s different works and how he was able to draw attention to his work through destruction.

I decided to move away from the snake idea we spoke about because I find dadaism very fascinating and I feel this would be a fun topic to continually work on leading up to the final essay.

Post exhibition burning. Xiamen Dada.

1. Zhi, Jiang. 2017. “Eyes Wide Open: How Chinese Contemporary Art Went Global | Christie’s.” Www.christies.com. 2017. (“publicdelivery.com”, 2022)https://www.christies.com/features/Art-and-China-after-1989-Theater-of-the-World -8579-1.aspx. (Jiang Zhi, “christies.com”, 2017)

2. Lin, Xiaoping. 1997. “Those Parodic Images: A Glimpse of Contemporary Chinese Art.” Leonardo 30 (2): 113. https://doi.org/10.2307/1576420.

3. Chong, Doryun. 2015. Review of Huang Yong Ping: Change Is the Order of the Day. Informit. March 1, 2015.

4. Holmberg, Ryan, and Huang Yong. The Snake and the Duck: On. Sept. 2009.

– This is a great .PDF excerpt that I found online from “Yishu: Journal of

5. “Huang Yong Ping’s Controversial Theater of the World – Public Delivery.” 2022. Publicdelivery.org. April 14, 2022. https://publicdelivery.org/huang-yong-ping-theater/#Who_was_Huang_Yong_Ping. (“publicdelivery.com”, 2022)

6. “Fei Dawei on HUANG YONG PING.” n.d. Www.artforum.com. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.artforum.com/print/202001/huang-yong-ping-81612.