My exhibition explores themes of female identity through the lens of the life and work of Pan Yuliang and other female Chinese artists.

In the early 20th century, China was experiencing radical social and political turmoil. This upheaval ushered in a change in women’s roles in society and the opportunities afforded to them. As a result of what is referred to as the 1919 May Fourth Movement, education for women became more attainable as, for the first time, co-education was allowed (Teo 2016, 39-41). With greater opportunities for women, came an increased awareness of their rights and social roles, now less restricted by traditional Chinese ethics (Li 2000, 31). Along with more freedom, women sought new ways to express themselves and discover an identity outside of being a mother, daughter, or wife.

Pan Yuliang was born in 1895, orphaned at a young age, she was considered a piece of property. She was sold and bought, eventually marrying Customs Official, Pan Zanhua as his concubine at only 18 (Andrews 1998, 178). Suddenly married to an official, her social status changed dramatically which afforded her the opportunity to pursue her talent for art. Pan grabbed the chance to go to the Shanghai Art Academy when education became co-ed for the first time in 1919 (Teo 2016, 41). She then traveled to Europe in 1921 on fine arts government scholarship as one of the first of the Chinese students to study art in France where she eventually made her home. It was rare at the time for women to achieve independent careers as professional artists (Ng 2019, 21-31). Pan Yuliang was a pioneer as both an artist and a woman.

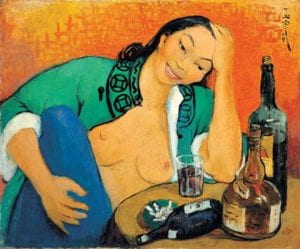

Pan painted thousands of paintings throughout her life in a wide variety of styles. Pan’s art reflects both her western training as well as her Chinese heritage, with some paintings in brilliant, vivid, fauvist styles and others in the more traditional ink on paper Chinese styles (Ng 2019, 21-31). The majority of her work, however, combines these two aspects of her life, both in technique and subject matter. Said subject matter is the most striking and revolutionary aspect of Pan’s work. The one uniting theme throughout all of her art is women. Pan painted women of all different backgrounds in various aspects of life. Over half of her paintings were non-white female nudes (Teo 2016, 57), embracing all flaws and imperfections in, not only the female body, but also their lives. Pan’s art is a rebellion against the commodification of the female body and an expression of a female identity. From her nudes to her self portraits, Pan strove to represent women openly and without shame.

Pan Yuliang, Artist Self-Portrait, 1963. Oil on Canvas, 80 x 65 cm. (Source: Teo 2016, 34)

Works cited:

Andrews, Julia Frances, and Kuiyi Shen. “The Lure of the West: Modern Chinese Oil Painting.” In A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China. Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1998. 172-78.

Li, Yuhui. “Women’s movement and change of women’s status in China.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 1, no. 1 (2000): 30-40.

Ng, Sandy. “The Art of Pan Yuliang: Fashioning the Self in Modern China.” Woman’s Art Journal 40, no. 1 (2019): 21–31.

Teo, Phyllis. “Pan Yuliang: The Misunderstood ‘Mistress’ of Western Painting.” In Rewriting modernsim. Three women artists in twentieth-century China: Pan Yuliang, Nie Ou and Yin Xiuzhen. Leiden University Press (LUP): Leiden, 2016.

The fact that Pan’s work emphasizes women, and not only their beauty, but also their lives, makes me realize that my artist, Feng Zikai, took a similar approach with his children and children in general. Art for children was not something that was common in Chinese art at the time. Feng not only painted cartoons of children and their lives, but some of his work was aimed directly for the young audience. His works were simple, colorful, easy to understand, and some were even put in elementary school textbooks. Feng thought this was necessary because there was little to no art dedicated to children. His works also emphasized the energy and the innocence of children, as well as the joy and hardship that they can bring to their parents’ lives. I would definitely include more about this in my project on Feng to highlight his contribution to the art world.