Do Facial Features Paint a Perfect Picture? Yue Minjun Thinks Otherwise

Facial features, specifically smiling and laughing, is often deceptive. Yue Minjun, a contemporary artist born in Daqing, China in 1962, has instituted an inventive and unique style for self-portraiture work. Yue graduated high school in 1980, and then attended Hebei Normal University, training as a painter, sculptor, and printmaker (artnet.com). In art school, he was influenced by the 1985 New Wave (a new art movement in China that shifted from Socialist Realism style) and the works of artists such as Liu Xiadong (a leading founder of the Cyclical Realism movement in China during the 1980s and 1990s), providing him with the groundwork for his future direction (Peng 2010, 943). In many of his works, Yue expresses beliefs about the historical and present day political and social system in China. My exhibition will focus on the following themes in Yue’s work, many of them overlapping with each other: stylistic features (facial expressions that Yue incorporates), the painting Execution and its similar counterpart (Francisco Goya’s painting May 3 in Madrid or The executions), the historical event(s) that influenced Yue (specifically the Tiananmen Square protests), along the artistic movement that Yue was the forefront of (Cynical Realism Movement). My exhibition will also incorporate works by Yue that share similar messages of suppression and social turmoil to that of Execution.

The act of smiling and laughing by the subjects in Yue’s paintings will be the primary stylistic component that I will be analyzing. Through painting and sculptures, Yue has created works that depict his own laughing figure in different iconic moments in history. The subjects in his painting often have a big, over-exaggerated smile on their face, bringing a comical dimension to the appalling situation they are in or are victim to. Yue’s smile is contagious, and the subjects he depicts are almost frozen in laughter, in disbelief about the absurdity of the situation that they are in. This sheds light on dysfunction in the country throughout varying periods, such as the Tiananmen Square protests and the rule of Mao and other political figures in the CCP. Essentially, smiles and laughter serves as a medium to describe the ridiculousness that Chinese citizens were facing in different time periods. According to Yue, “at first you think [the person] is happy, but when you look more carefully, there’s something else there…a smile doesn’t necessarily mean happiness; it could be something else” (Bernstein 2007). Moreover, repetition in Yue’s work is key. The consistency and repetition of facial features in his work intensifies the postmodern melancholy in the nation, while also serving as a reminder of the everyday struggle that Chinese citizens face.

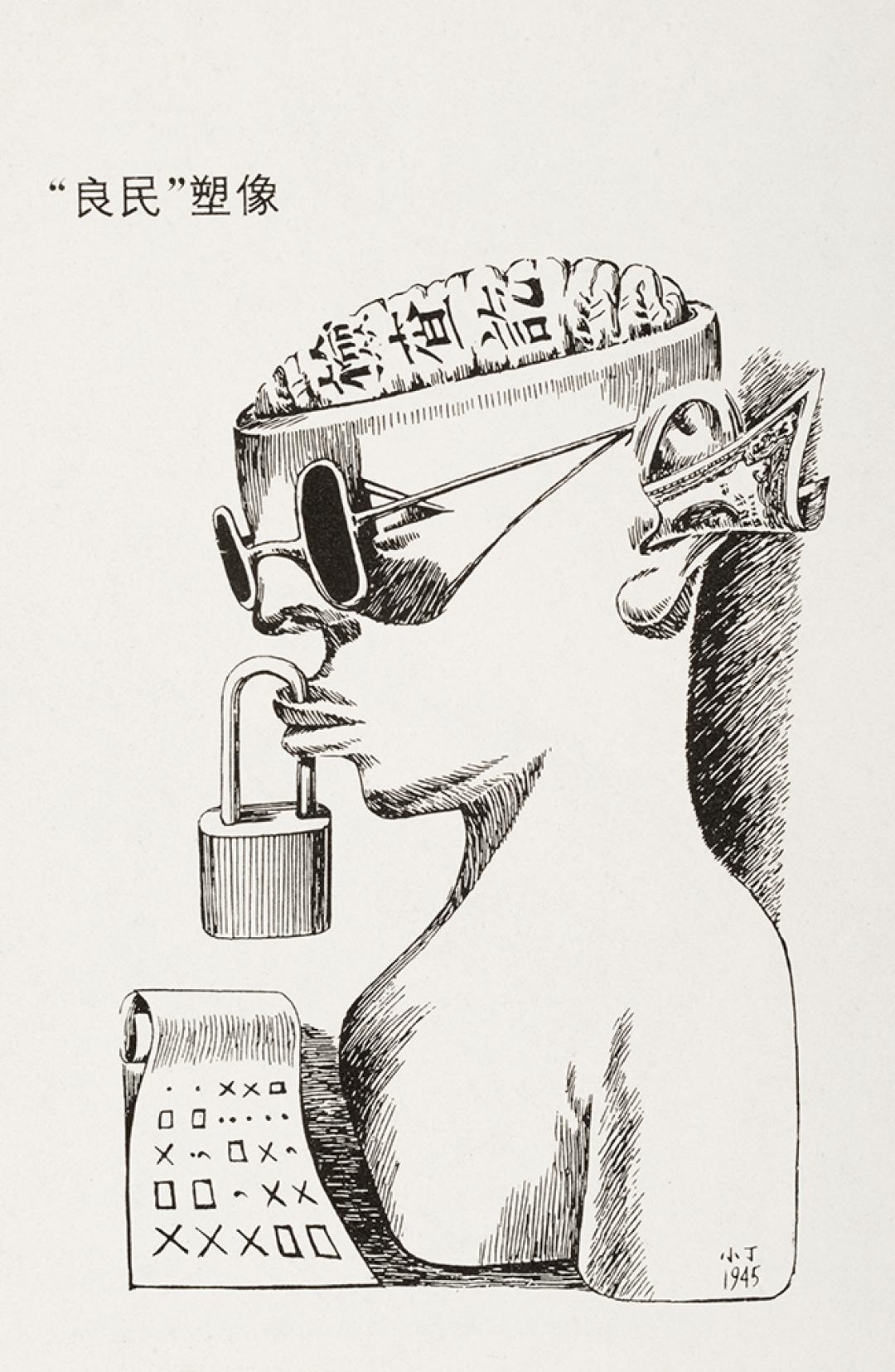

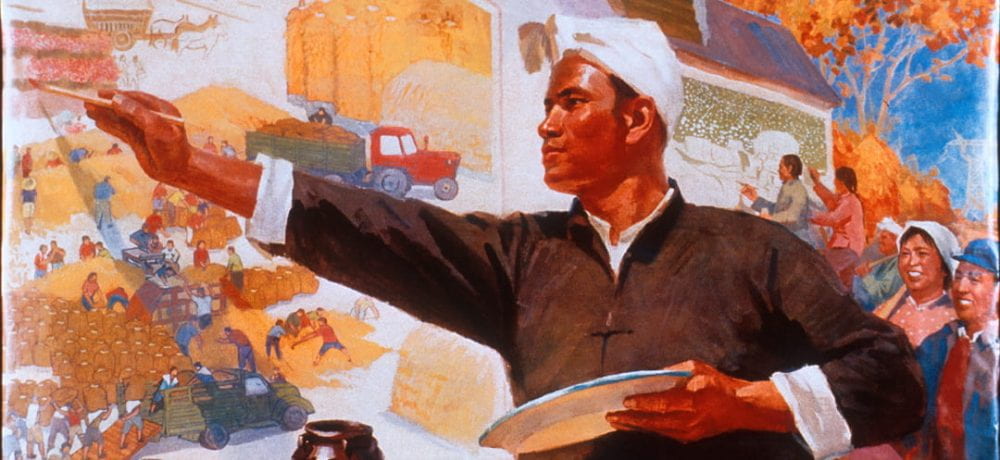

In addition, the theme of powerlessness is applicable in many of Yue’s works, including Water, a 1988 oil painting that depicts Mao enclosed in a swimming pool inside the brain of the subject. In Water, Yue is trying to amplify the fact that Chinese citizens are like a puppet to Mao and the CCP. This painting is one of many that Yue has created to further personify the manipulation and helplessness that Chinese citizens face.

In respect to the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, this historical event had a distinctive influence on Yue’s work. Yue was disgusted by the restrictiveness of the Deng regime in China during the 1980s, and the tyrannical violence displayed by the Chinese government during the Tiananmen Square Protests stimulated Yue’s initiative to challenge the political hierarchy in the country. Moreover, this massacre ignited the Cynical Realism Movement beginning in the 1990s. Yue has had a lasting impact on the Cynical Realism Movement in China (although he rejects this acknowledgment) (artnet.com). The Cynical Realism Movement is a contemporary art movement that emerged in Beijing, promoting individual expression with less limitations. Many perceive Cynical Realism as an alienated reality of surrealism. This movement emphasized the utilization of “political pop.” The political pop that developed during this movement often challenges the political and social system in the country (visual-arts-cork.com). Further, Cyclical Realism was the spiritual product for a dismantled psychological state of the Chinese people (Peng 2010, 941).

Lastly, Yue’s oil painting Execution broadcasts its powerful message through content, colors, composition, and subjects. This painting illustrates the Tiananmen Square massacre. The declaration of martial law on June 4th, 1989 enabled the government to partake in immeasurable and unnecessary violence, by equipping troops with assault rifles and tanks. What started as a vehicle to convey political expression, quickly escalated into a bloodshed event that further suppressed Chinese citizens’ civil rights. Comparing Execution to Goya’s 1814 painting May 3 in Madrid or “The executions,” Yue’s painting resembles almost identical components to Goya’s. In both paintings, suppression and political controversy are an apparent theme. In respect to Goya, he based his work on the Spanish resistance of Napoleon’s army in 1808, where innocent Spaniards were murdered by the French (Museo Del Prado).

Yue Minjun (b.1962), Water, 1998, oil on canvas. Image source: publicdelivery.org

Yue Minjun (b. 1962), Execution, 1995. Oil on canvas, 59 x 118 in. Image source: Forbes.com.

Francisco Goya (b. 1776) May 3 in Madrid or “The executions,” 1814. Oil on canvas, 8′ 10″ x 11′ 5.” Image source: museodelprado.es. Museo Del Prado, Madrid, Spain, room 064.

Work cited

Bernstein, Richard. “An Artist’s Famous Smile: What Lies Behind It?” New York Times, November 13, 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/13/arts/design/13smil.html.

“Cynical Realism (1990s).” Cynical Realism: Chinese Contemporary Art. Accessed April 8, 2020. http://www.visual-arts-cork.com/history-of-art/cynical-realism.htm.

Lü Peng. A History of Art in 20th-Century China. Milano: Charta, 2010.

“Yue Minjun.” artnet. Accessed April 8, 2020. http://www.artnet.com/artists/yue-minjun/.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A334486089/LitRC?u=nysl_ca_unionc&sid=LitRC&xid=4292b9f5

“The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid, or ‘The Executions.’” Colección – Museo Nacional del Prado. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/obra-de-arte/el-3-de-mayo-en-madrid-o-los-fusilamientos/5e177409-2993-4240-97fb-847a02c6496c.