The 20th century in China is dominated by political and government changes that was shaped from their prior history. Art was greatly effected by these changes, whether it was the subject of the paintings or drawings, or the style of art, or the techniques used in each work. These changes were both voluntary and involuntary, depending on who was the leader of the country throughout the 1900s. One artist that spoke out against the forced change was Ding Cong, and through his political drawings, his message of exposing government corruption, along with illuminating realities that China faced, was widely known.

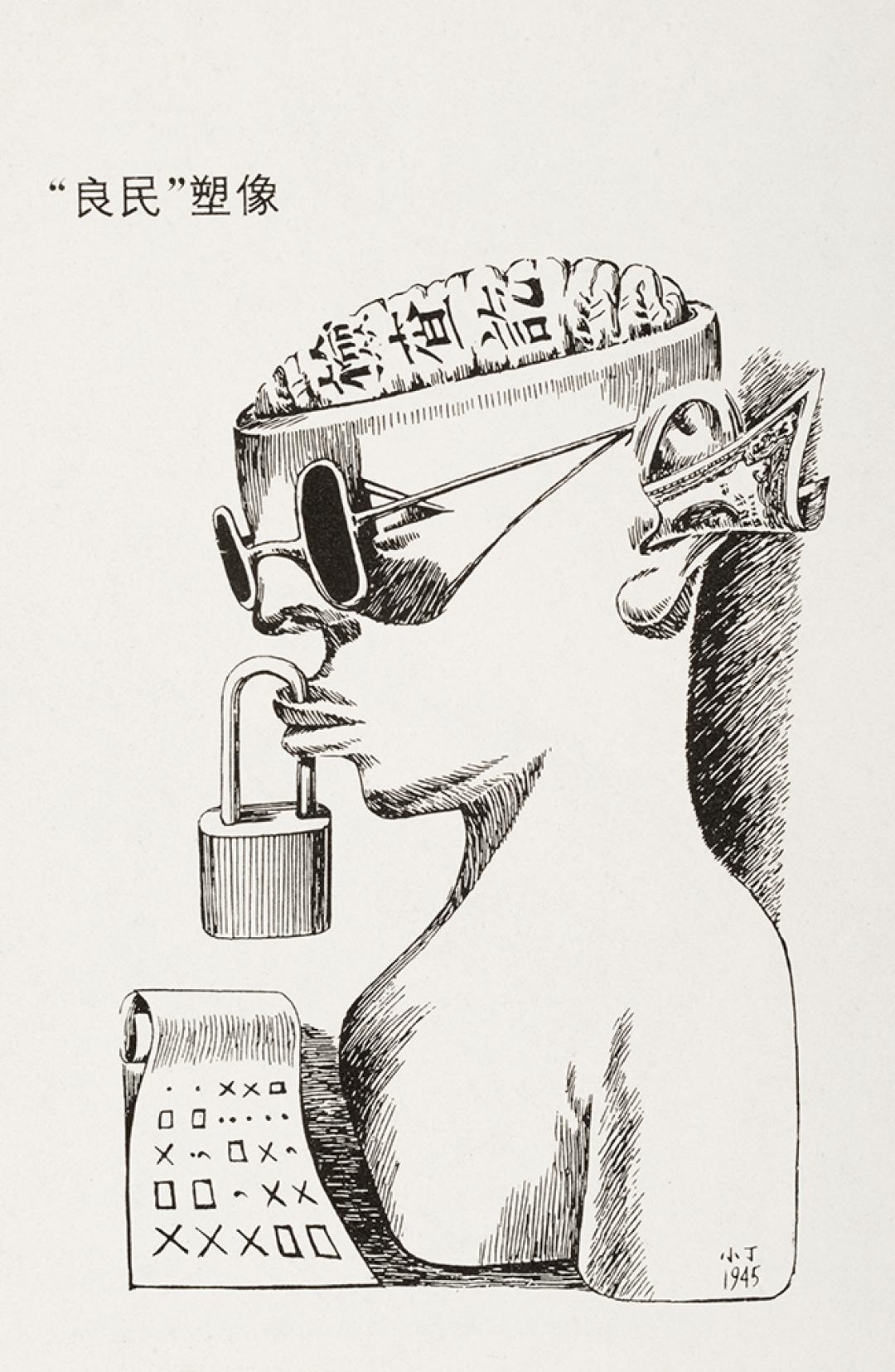

Ding Cong, also known as Xiao Ding (Little Ding), created many drawings over his career that shed light on what the average Chinese citizen was experiencing, and after the Sino-Japanese War, many Chinese, including Ding himself, struggled to survive during a period of rampant inflation (Ristaino 2009, 60). A few of his drawings represented the incredible inflation, with some drawings referring to national and abroad problems associated with it. Ding extensively drew upon the rampant corruption, market chaos, uncontrolled inflation, and abject poverty and unemployment that plagued Chinese citizens in his drawings. His signature stylistic trait that most of his art had were contradictions in society – depicting rich and poor or abuser and abused – to portray a country in morale decline (Ristaino 2009, 62). One drawing, that was published on the cover of a popular Shanghai magazine Zhoubao (Weekly Magazine), called “The Perfect Citizen” (1945) highlights the different ways the Nationalist regime would censor the population. The figure has his brain opened for brainwashing, his ears plugged with bribes, his eyes shaded by sunglasses, and his lips locked together (Ristaino 2009, 63).

My theme will present works by Ding Cong that show the changing environment Chinese citizens faced throughout the civil war (1945-1949), the Anti-Rightist Movement (1957-1968) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). My hope is to arrange pieces in a way to show both differences and similarities between the time periods through Ding’s work.

“The Perfect Citizen” (1945)

Ristaino, Marcia R. Chinas Intrepid Muse: the Cartoons and Art of Ding Cong. Warren, CT: Floating World Editions, 2009.