Experimentation pertaining to the modeling of speech production has a long and varying history. In fact, the first physical model of human speech production was built in 1771 by Eramus Darwin (grandfather of famous Charles Darwin). His model took the form of a machine that could pronounce four simple words: ‘mama,’ ‘papa,’ ‘map,’ and ‘pam.’

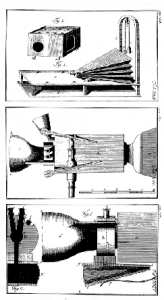

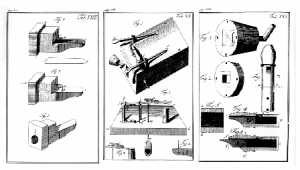

In Denmark around the same time, Wolfgang von Kempelen was developing a speech synthesizer that created vowel sounds via resonance tubes connected to organ pipes. Many decades later in 1791, his book was published elaborately detailing how to replicate his speech machine. It is still preserved to this day in the Deustches Museum in Munich.

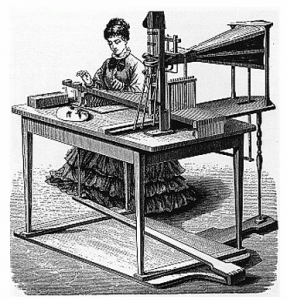

In 1846 in London, Joseph Faber made further progress with a machine that included a modeled tongue and pharyngeal cavity both of which could be manipulated. The machine was controlled with a keyboard and pedals much like those of a piano.

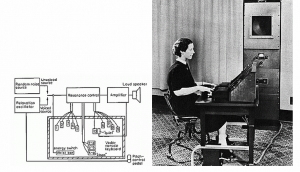

It wasn’t until the twentieth century that the field of electrical engineering became involved in the process of synthesizing speech sounds. Homer Dudley presented his VODER, which used electrical signals to generate sound, at the World Fair in New York in 1939. Although more often used for entertainment, like Kempelen’s machine, the VODER provided serious motivations for the continuation of the speech acoustics field.

Over the next several decades years, scientists continued developing other physical speaking machines in various forms. In the late 19th century it was discovered that vowels could be produced by combining energies at what we now called the vocal tract’s resonant frequencies or formants. At the tail end of the 20th century, software formant synthesizers were the most common. Over the years of experimentation and research, the governing factors of the design process shifted, depending on the specialty of the scientist. This variety is still present in modern day speech synthesizers. Some model designs are based on the underlying acoustic principles of speech production, while others are based more on the anatomy of the vocal tract and the controlling muscles.

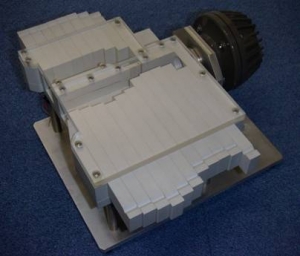

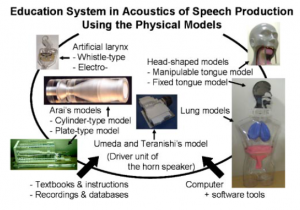

The fact that each of these models aims to explore a different feature of speech acoustics and production is extraordinarily beneficial to the notion of educating students via these physical representations. In 2007, Arai and colleagues published a paper outlining a comprehensive and inclusive education system which utilizes an array of vocal tract models. The education system includes models of the lungs, the replications of Chiba and Kajiyama’s models that Arai built, a model built by Umeda and Teranishi in 1966, and a simple head-shaped model with vocal tract and nasal passages. Umeda and Ternaishi’s model, which includes the effect of a nasal branch, allows for the cross-sectional area of the tract to be changed by sliding 10mm thick plastic strips. This model is unique in that it allows for transient sounds to be produced by moving the strips while the sound source is supplying an input stimulus. Arai notes that creating perfect diphthongs (single sounds formed by the combination of two vowel sounds) was difficult but still a function other models do not possess.

Arai’s education system includes a head-shaped model to supplement these otherwise straight line models. The head shaped model allows for students to orient the vocal tract as it is actually situated in the human body.

This video, taken from Arai’s website, demonstrates several of the models pictured above and highlights the cylinder type models that inspired this project. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uihcYEG4vgI