This exhibition is mainly about Liu Haisu’s experimentation in both western techniques and traditional Chinese paintings. As one of the earliest Chinese artists who had influenced by western art techniques, Liu Haisu spent his caareer tried to cross the boundry between Western oil paintings and traditional Chinese paintings, and his art had several evolutions under different historical contexts from his early years to late years.

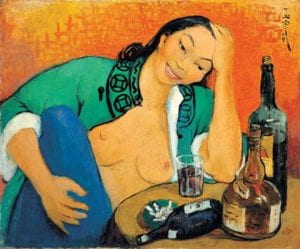

Liu Haisu was born in 1896 and started being influenced by western art when he was a teenager. One of the most significant controversies in his early years was that he was criticized “traiter in art” when he was doing nude figure studies, and since that Liu Haisu had been the rebellious artist who broke the rules for hundreds of years and was aim to find new possiblilities for tradtional Chinese art under the influence from Western art techniques and so as Western art development in China. Liu visited Japan for the first time in 1918, which was the time he had chance to learn about Western modern art concepts such as Impressionism and Postimpressionism systematically, and he started promoting Western art education in China since then. Liu Haisu lived 98 years, so he had quite a long career as an artist, and he lived in serveral different social contexts in Chinese history, which made his works distinct from different periods of time.

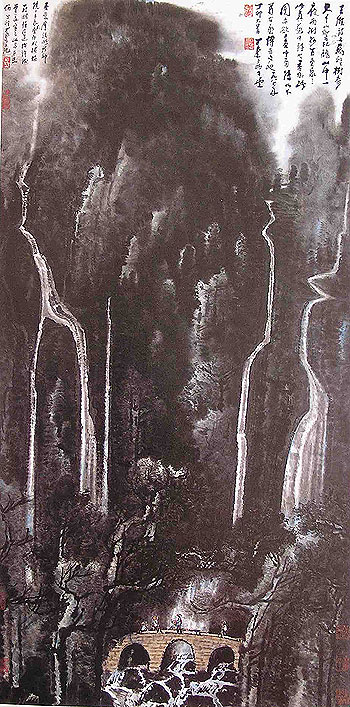

During the late years of Liu Haisu’s career, he did not stop explration, but kept breakthoughing his own art concepts. One example we are going to discuss was made in the late years of Liu’s career, from which we are able to see Liu’s style after decades of development and evolution in his own concept, which was sigmificantly influanced by both western art and traditonal Chinese culture. “Lotus Peak of Yellow Mountain” was made by Liu Haisu at his seventies. At this stage, Liu had be so maturaly using both Chinese and Western painting techniques, that the “rules of art” had been something restricted him from kept breakthroughing. Unlike the paintings from Liu’s earlier years, the brushwork was weaken in this painting; and Liu tended to animate the landscape, light and shadows by jaxtaposing ink wash and blank paper. And from this painting, the audience are able to see the change in Liu Haisu’s style in his late yrars and that Liu never stopped art exploration as an artist who spent most of his life as a pioneer of Chinese modern art.

“Lotus Peak of Yellow Mountain” by Liu Haisu

“Lotus Peak of Yellow Mountain” by Liu Haisu

References:

Xiaoping, Lin. “Contemporary Chinese Painting: The Leading Masters and the Younger Generation.” Leonardo 20, no. 1 (1987): 47-55. Accessed May 11, 2020. doi:10.2307/1578211.

“Painting Academies and Western Influence.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 58, no. 3 (2001): 20-25. Accessed May 11, 2020. doi:10.2307/3269183.