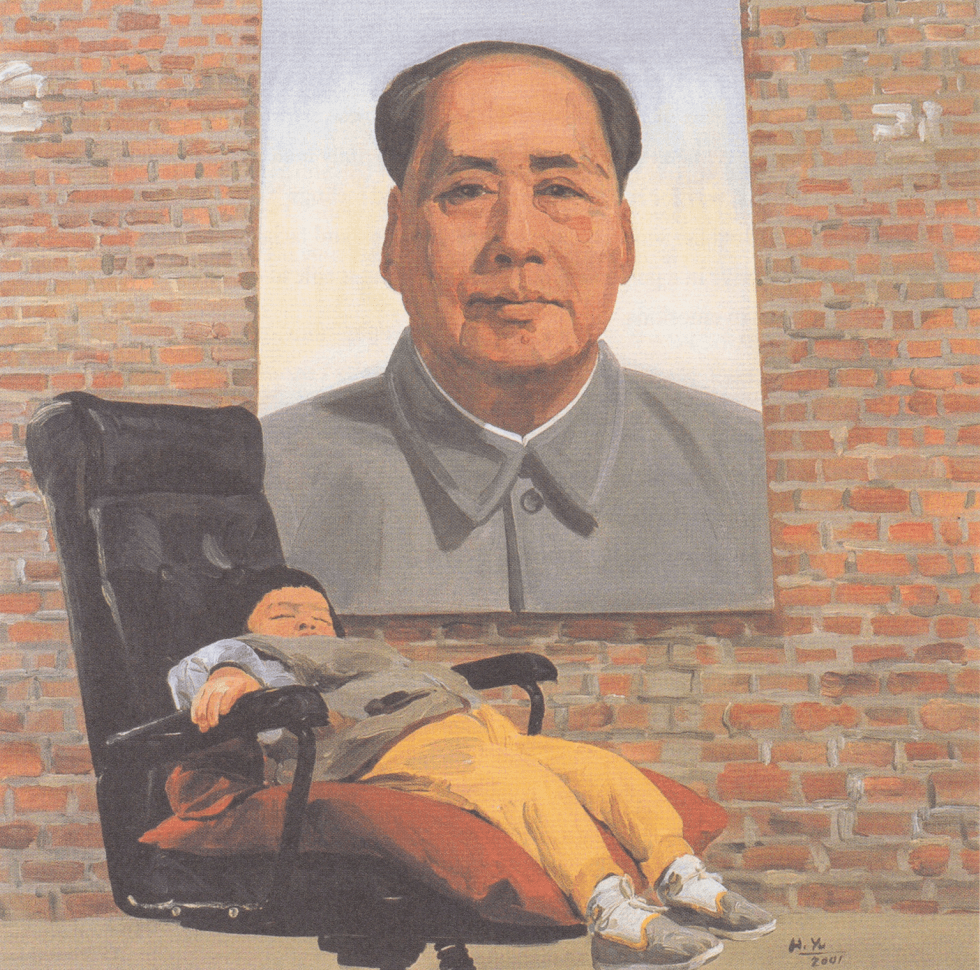

Liu Wa Two Years Old, Oil on Canvas

Image Source: Piëch, Xenia. “Yu Hong’s Witness to Growth: Historic Determination and Individual

Contingency.” Academia. September 2003.

Yu Hong was trained in socialist realist style painting at the Central Institute of Fine Arts in Beijing, China. However, Yu breaks away from painting idealized versions of society and instead depicts the need for social reforms. She specifically relates her art to the constricts of women in traditional China and the search for female identity. Yu Hong created the series Witnessing Growing Up in 1999, a commentary of her life growing up in a highly socialist era (Wang, 31). She created the oil on canvas Liu Wa Two Years Old, a painting of her daughter. Yu had entered a new phase of her life that she wanted to represent, specifically focusing on her child’s individual growth and development in society (Piëch, 35). Yu intentionally used oil to represent the realistic features of the space. She emphasizes shadow and lights to emulate the realistic nature of the bodies. Additionally, she paired each painting in this series with a photograph gathered by the People’s Republic. She then exhibited the photograph next to the rectangular oil on canvas to allow the viewer to understand the political situation at the time (Piëch, 36). The photograph paired with this piece was a villa complex in Beijing; a dream of hers at the time to live there. Additionally, her piece depicts a large painting of Mao hung up on a wall in someone’s home, a typical trait of a social realist painting. However, in front we see Yu’s young daughter in a chair slumped taking a nap. Yu Hong was born at the height of the cultural revolution, a time where everyone had a portrait of Chairman Mao in their homes. However, here she is contrasting her childhood to her daughters. In a previous painting, Yu paints herself as a child smiling with a Mao Badge on her arm. On the contrary, her daughter is blissfully sleeping away from one of the most influential role models of Yu Hong’s childhood. Additionally, Yu uses a bright yellow on her daughter to represent that calmness and happiness of her childhood. Underneath her daughter sits a red pillow, an ironic comment of the revolution due to the color (Piëch, 37). The viewer is able to interact with this multidimensional painting because of the different planes in space. As a viewer we feel comfortable in this spacious home even though a large painting of Mao dawns over us.

Bibliography

Piëch, Xenia. “Yu Hong’s Witness to Growth: Historic Determination and Individual Contingency.” Academia. September 2003. http://www.academia.edu/11968321/Yu_Hong_s_Witness_to_Growth_Historic_Determination_and_Individual_Contingency.

Wang, Qi. Memory, Subjectivity and Independent Chinese Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014.