I recently went to the Pushkar Camel Festival. Pushkar is a small town in Rajasthan, about 2 hours from Bagru.

Pushkar is a very holy place for Hindus. There is a small lake in Pushakar, which is said to be made from the tears of Lord Shiva’s wife after he died. Additionally, Pushkar is home to one of the only Brahma temples in the world. Brahma is known as “the creator” in Hinduism – part of the Holy trinity in Hinduism.

I know it’s easy to get lost in the names and Gods of Hinduism, so I’ll spare the complexity by saying this in laymen terms: Pushkar is a very, very holy place.

For hundreds of years, every November, Pushkar has been a site for camel and cattle traders to assemble to buy/sell their livestock. In that sense, not much has changed; many of the camel tradesmen have no relation to the “festival” that is advertised for the many tourists in India. For the camel traders, there are no set dates, but as the November days progress, hundreds of thousands of camel traders arrive from all over India. Alongside this special occasion, there hundreds of thousands of tourists who come to watch this ordeal, see the camels, and enjoy the “fair” events, i.e. an amusement park at night and different cultural dances.

My first reaction when arriving to Pushkar was that the fair wasn’t really for “me” – as a tourist, I was just an observer of the real event, where the camels were being traded. For example, although there were many shops targeting tourists, they were greatly outnumbered by shops for the camel traders; here, traders could buy camel saddles, ropes, farming tools, etc. I felt as though I was walking through the world’s biggest marketplace for ‘camel people.’ The most refreshing part of this was that nobody was approaching you to buy anything or haggling you. I was just a ghost wandering in the sand dunes, observing a different world, unbothered and unseen.

Pushkar is a very small place that gets flooded with people for the month of November for the camel fair. There’s only about 12,000 year-round residents – half the size of Bagru! But, throughout the year, devout Hindus visit Pushkar to visit the Brahma temple and bathe in the lake. Even though the water is murky and littered, you can always find people stripping down and wading in the holy water.

So, what can you learn from this? I found Pushkar to be fascinating for a very distinct reason: coexistence. During the camel fair, there are three specific groups of people in the town, living together in a chaotic harmony.

- The camel traders and their families

- Religious Hindus visiting Pushkar for the temple and lake

- Tourists, like myself.

Coming from a religious village like Bagru, I felt comfortable among groups 2 and 3. Since I’ve learned a lot about Hinduism and feel comfortable in Hindu temples, I could personally even feel a palpable spirituality in the holy Brahma temple.

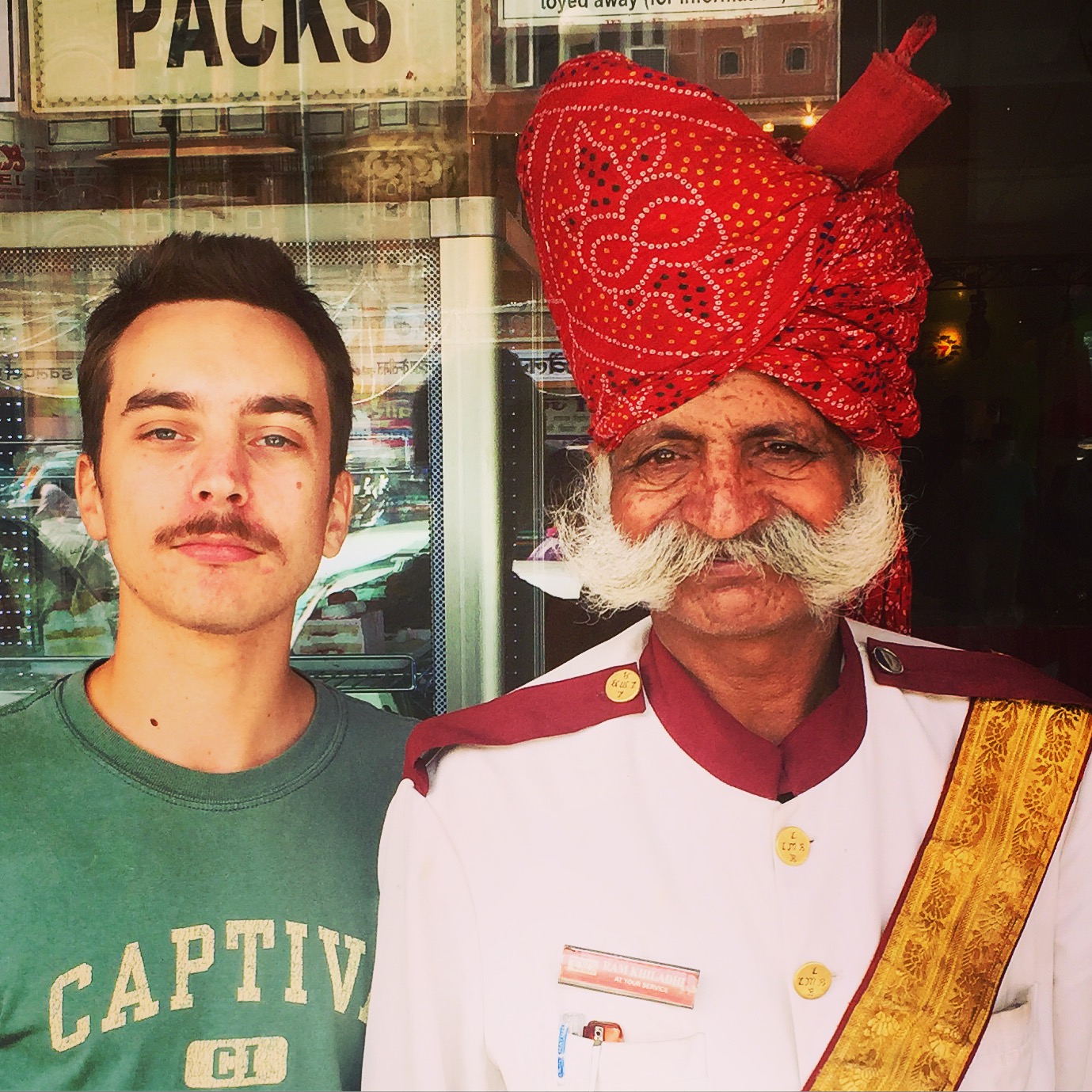

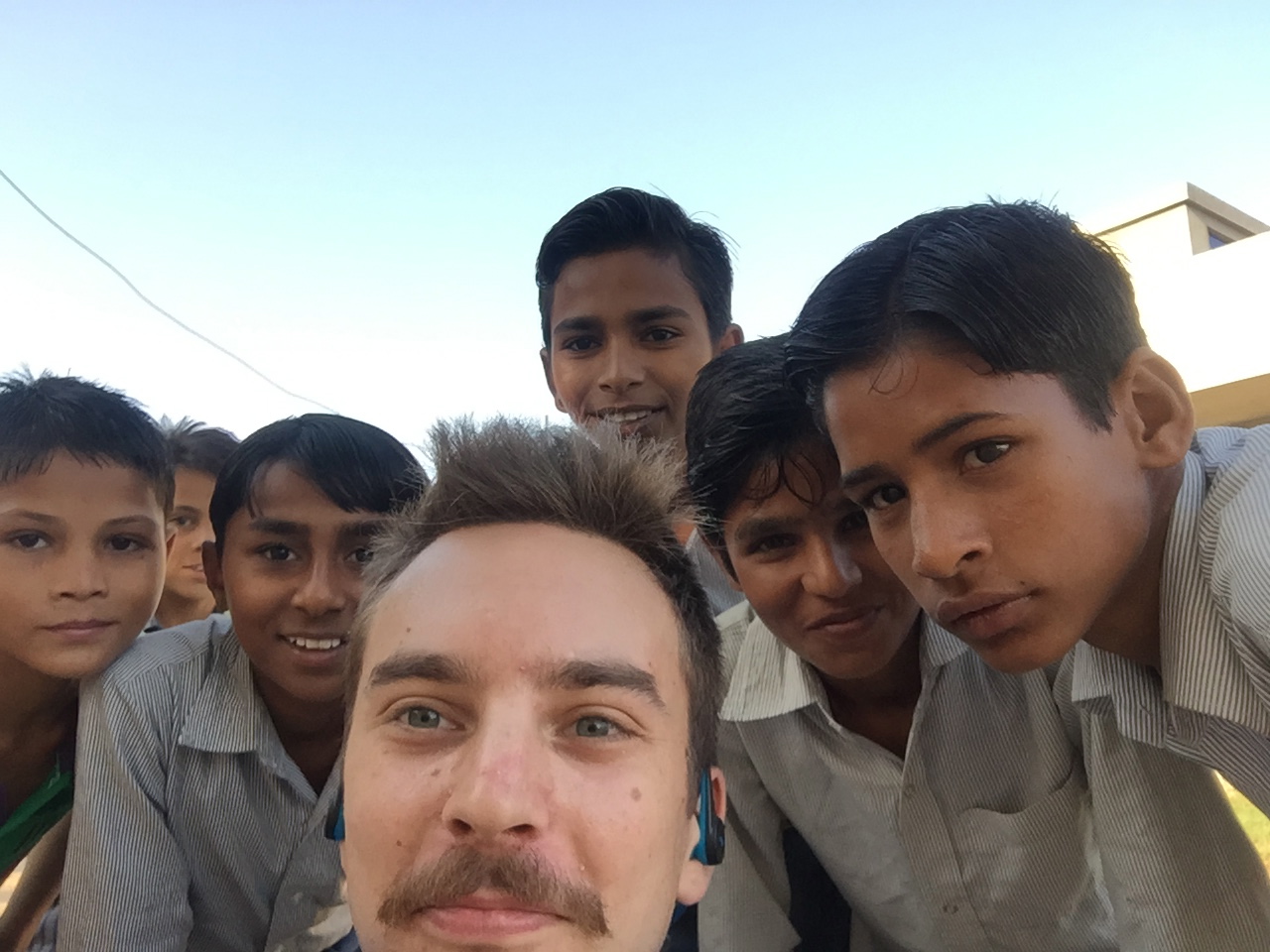

With that said, I am the only foreigner in Bagru; I’m not used to seeing thousands of white people walking amidst ‘traditional’ Indians from Rajasthan. Then, to add the whole camel people to the equation, (one might call them nomads) was a beautiful cultural clash.

I’ve been trying to equate my experience at the Pushkar fair to something I’ve seen in America. The truth is, nothing like it exists – not because of the lack of camels, but due to the void of cultural acceptance.

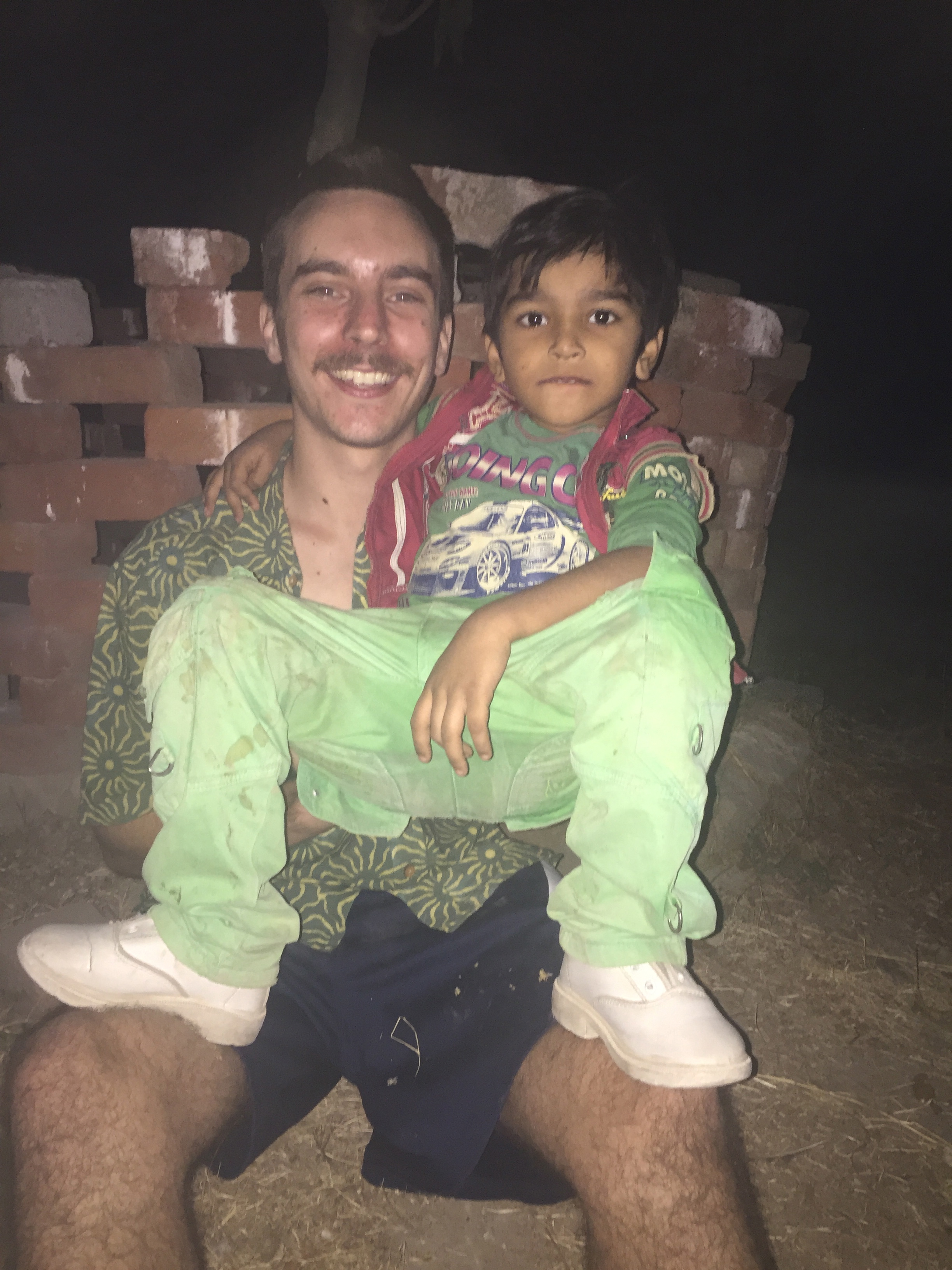

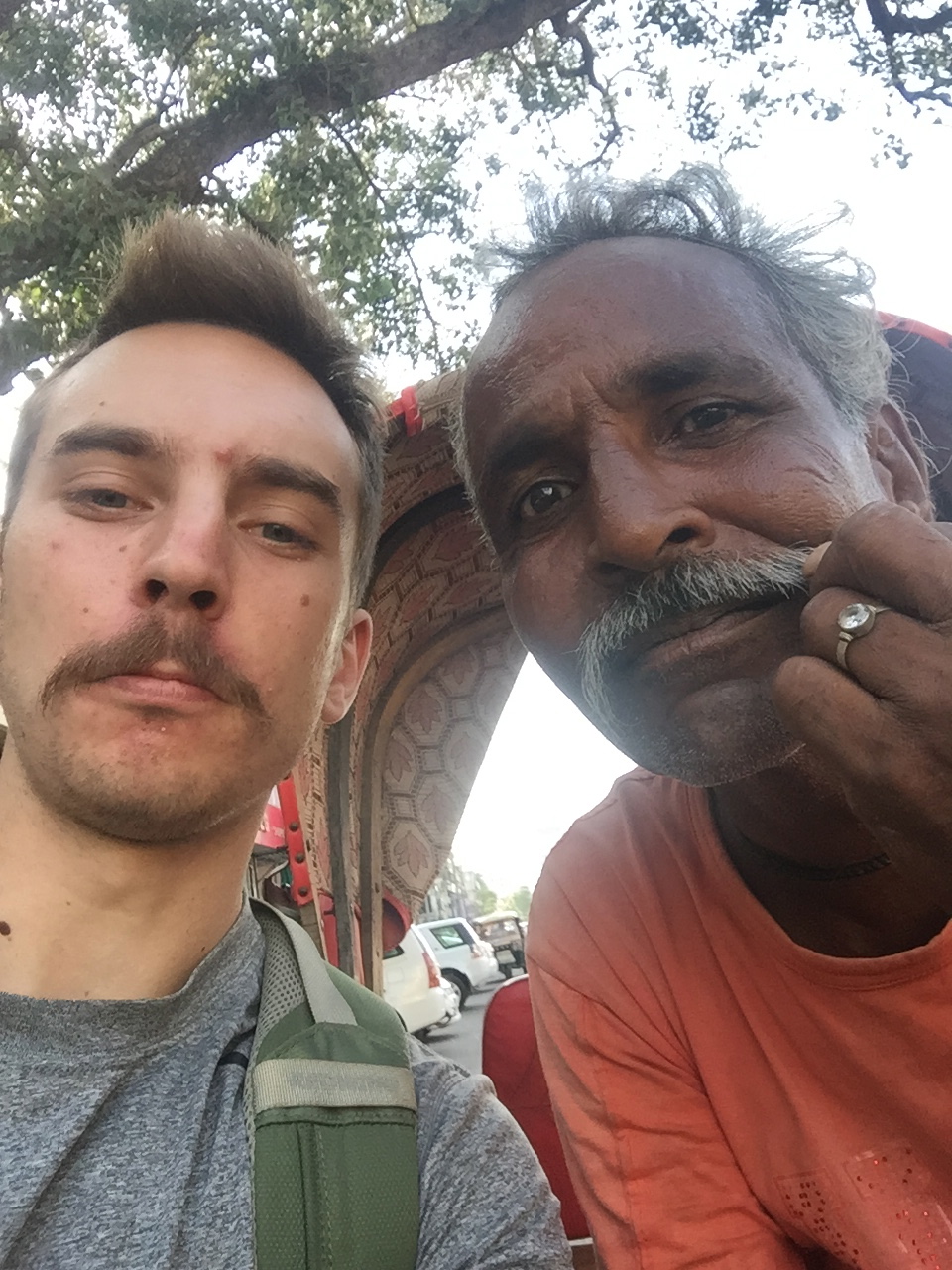

In Pushkar, nobody seemed to mind what your business was. The streets were filled with half-naked gurus, hippie stoners from Israel, National Geographic photographers, camels, horses, and farmers who clearly hadn’t bathed in weeks. Nobody cared.

I can only imagine the political fallout or potential for violence this type of scenario would pose back home. Imagine a gathering with rich elites from New England, some ‘thugs’ from Oakland, and a community of Amish. And, let’s say it took place in a redneck town Alabama. Seriously, what the hell would happen?

Obviously this is hypothetical, but I couldn’t help but notice how invisible I felt in Pushkar, despite my utter contrast to those around me. It was refreshing.