I used to have this theory of equilibrium: all people, no matter where they are from, come out even in life. Essentially, for every hardship one encounters, a balancing positive will arise. This was my way to justify anything I saw in life as ‘unfair’: death of a family member, children with cancer, homelessness, or rejection. As an adolescent I truly believed this formula worked – if you lose a loved one, you will meet another to love. If you were poor and hungry as a child, perhaps the strength gained from that experience transforms into a successful adulthood. It’s a naïve formula that I no longer believe in. Let me tell you why.

This world is far from balanced. Most of us can’t ‘balance’ work, play, and family. I surely can’t balance a checkbook; hell, the ‘balanced’ diet you’re following is probably protein or carb-heavy. More poignantly, there is an innate disparity – a lack of balance – between social classes here in India.

Our journey on the mini term directly introduced us to India’s multitude of faces. I realized slowly that, while I thought I really understood India, Bagru does not, and cannot, explain Indian culture as a whole. Truthfully, it barely scratches the surface of rural India, without even touching on the differences with the urban. I’m currently sitting in a café in Mumbai that feels worlds away from Bagru – even New Delhi for that matter.

Going back to balance. The best forms of government create balance. This is playing out perfectly in the American election cycle right now, where ‘inequality’ is one of the most commonly used words on the campaign trail (aside from “boots on the ground.” Yes, I’m talking to you Ben Carson). The roots of imbalance are vast, ranging from crony capitalism to corruption and, in India, caste. Stability and balance are essential for functionality between families, socioeconomic class and businesses, between religions, political parties, and ourselves. In addition, balance is a key indicator to quality of life. It’s no secret that Scandinavian countries have the lowest Gini coefficient, (measuring economic inequality) and also the highest quantifiable quality of life.

While wealth is a main contributor to this hypothesis of balance, I’m not only talking about economic inequality.

On our last night in Mumbai we went to the rooftop of the Four Seasons hotel for a goodbye drink. The Four Seasons is the nicest hotel in Mumbai in the center of the city. The setting was picturesque. We looked out on a beautiful orange sunset backlit the skyline before us, the sun dipping below the ocean horizon for as far as we could see. As my eyes wandered down however, I descended upon the slums directly below. As I sipped my drink, millions of people living off less than $4 a day were staring up at me. I was wondering what they were thinking.

Only days before, we were on a tour of Dharavi, one of the largest slums in the world – home to 1 million people, and the location of Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire. As I walked through the narrow alleyways of filth and gut-wrenching odors, I was fascinated by the organization and lifestyle of the slum, but less concerned with the poverty. After all, I’ve seen slums in Cape Town, South Africa before, and I’ve lived with amidst poverty for the past five months. What bothered me more was where I was going – after I left the slum.

I had seen the way the inhabitants of the slum were looking at me before; it is the same way our printers in Bagru look at our foreign clients or tourists passing by. It’s not a look of hatred or jealousy, but rather pride. It’s a look that says, “you couldn’t live here if you tried,” or “you wouldn’t understand what I’ve been through,” or “have fun at your hotel. I’ll still be here.”

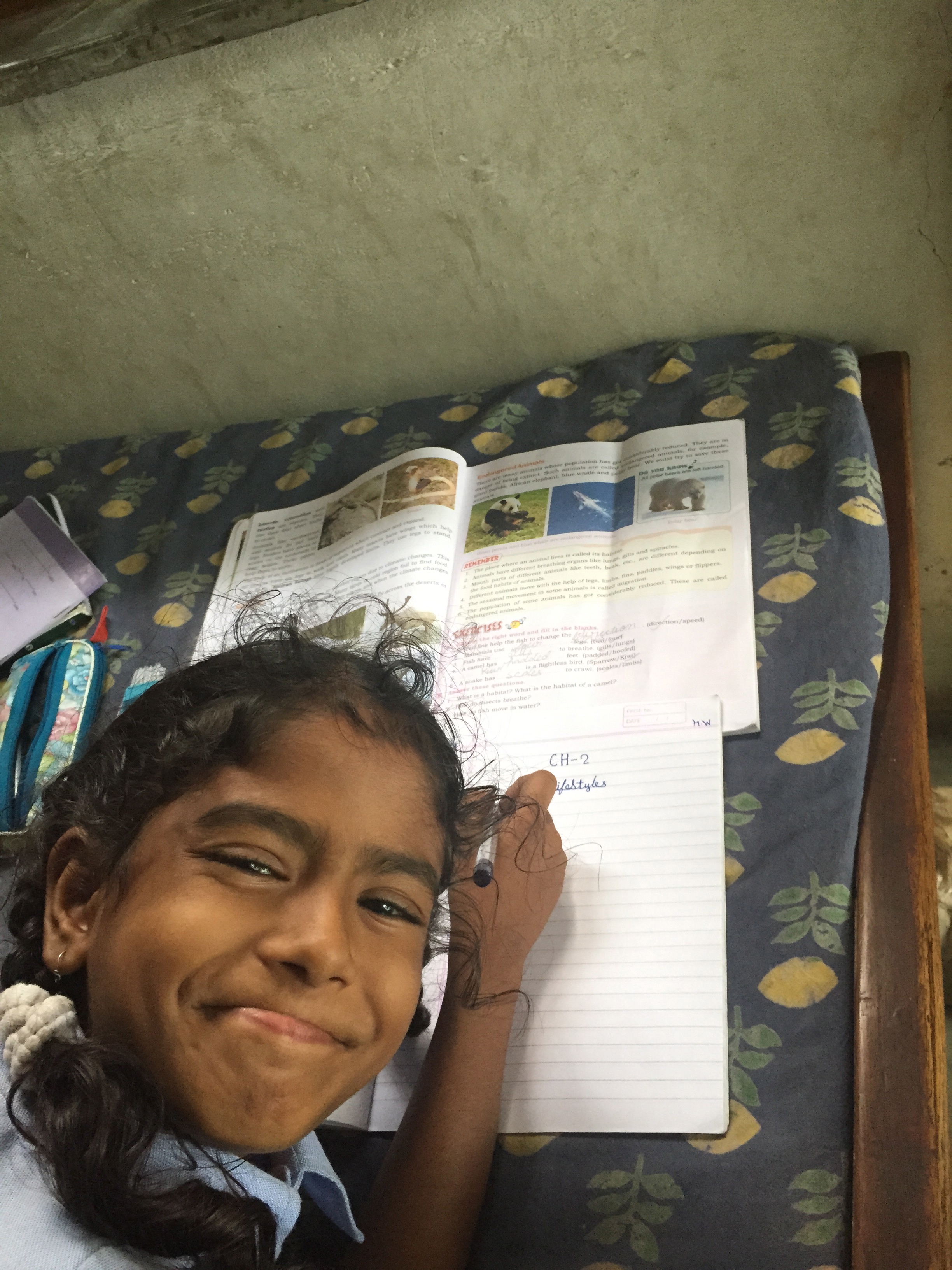

From my experience, most poor people aren’t ashamed of what they have – they’re proud of themselves for persevering and succeeding with the cards they’ve been dealt. Now, that is an admirable quality.

There is a distanced relationship between the passerby and citizen, where respect must be earned, not given. I wanted to stand there in the Dharavi slum and tell them that I can do it. I want to live with you. But, at the end of the two-hour tour, we boarded our coach bus and went to Starbucks, shopped around a mall with Gucci and Rolex stores, and slept in our hotel with fresh linens.

I’ve found it amusing yet perplexing that I’ve been able to seamlessly float between the rich and poor of India. I’ve seen arguments in Bagru about purchasing a 5-cent pencil. I’ve even screamed about 2 cents with a rickshaw driver. I’ve legitimately fired a printer in Bagru who make less than $150 a month, and gone to malls in Mumbai that are no different from American luxury. I’ve felt comfortable in both circles. Now I’m having trouble deciding to which I really belong.

I feel more unbalanced than ever before, like a swinging pendulum that shifts every second. Union seems closer than ever, but miles apart.

If you were to ask me if I could pinpoint 1 skill since I’ve been here, what would it be? My answer would be this: if you were to drop me in any village in Rajasthan, India, I would have no problem walking around and making friends. I wouldn’t feel intimidated approaching a Chai stand with ten Indian men with fabric wrapped around their heads, shooting the shit in Hindi. It’s an intangible skill that I’ve developed, a certain second-hand nature of how-to-act and what-to-do. Yet, at the end of the day, what does this really get me?

On the contrary, if you were to drop me in any poor neighborhood in Chicago or Detroit, I would feel lost and foreign. I’ve found a sense of belonging in a very particular place in the world – a very specific place in India. Now, I’ve been on the other side of the swinging pendulum; in Mumbai, I’m just another dude.

I’m still trying to find the balance. So is India, and America, and each one of us.