All posts by cutterd

The Yatra Files (2/4): Basic Recap

The Jagriti Yatra

15 days

12 destinations

8 Role Models

5,000 miles

1 country

1 train

450 Yatris (participants – from nearly every state in India, and 23 countries).

Physical Conditions

I lived on a train for 15 days. If you have never been on an Indian train, that sentence doesn’t do much justice. Government-run sectors in India are overrun, dirty, outdated, and unorganized; the Indian Railway system is no exception. I’ve heard foreigners refer to Indian trains as “prisons” – their steel bars as windows, 5-foot bunk beds stacked 3-high, and a “catering service” that is reminiscent of death row.

If you’re a germaphobe, an Indian train is you’re worst nightmare. The word “clean” now has different standards. A friend living in Jaipur recently joked that the most germ-infested places in the world are door-handles on Indian trains. General sanitation in India is noticeably different from Western standards. On the train, food servers would walk the aisles passing out food with their bare hands. Nothing like the server sticking his hands deep into a giant vat of sliced cucumbers and tossing a heap on your plate. Again, there’s no choice but to put the cucumber in your mouth. You just do it. For my fellow Indian Yatris reading this, I’m sure you’re laughing. These are such negligible details about the train, but they stick out for a foreigner like myself.

Many Indians were impressed by the way many foreigners were handling these differences. While I had been on an Indian train before, I too was a bit taken back by these harsh, grotesque, realities. Yet, to be blunt, I had no other choice. There was nowhere to hide, no food alternatives, nowhere quiet to clear your head for five minutes, no real showers, no clean toilets, or first class amenities. Sometimes you just do things, and you come out stronger on the other side.

There was nowhere to escape, which made the experience more unique. I have no voice from talking for 15 straight days. As a person who enjoys from privacy, there wasn’t a chance to even read in a quiet place, or just sit and think. Thinking became a communal activity; we built trust within days, and broke privacy barriers immediately.

Layout of train:

There were a total of 450 “Yatris” – participants like me, 100 food staff, 30 volunteer staff, and 15 full-time Yatra employees. Maneuvering, feeding, and pleasing 500+ people on a train – from all different backgrounds – was a logistical nightmare. Train delays were a common occurrence, even for eight-hours on our final day.

Even moving around the train was a challenge. Simple things required planning and patience. With one sink shared between 40 people, brushing your teeth was a process. There were often four people huddled around the sink at once – one soaping their face, one shampooing their hair, one brushing their teeth, and the other applying toothpaste. Maybe even another trying to gel/oil their hair in the mirror. To change clothes, you had to displace four people to stand the aisle, causing a traffic jam and people yelling “Side, side, side” to allow them to pass. Going from one end of the train to the other took nearly fifteen minutes (not counting any stops for conversation). It was often a relief to finally get back to your “bed” after venturing to the other side of the train.

What we did:

Role Models and Yatri Interactions: The Jagriti Yatra brought us to 12 accomplished “role models” around India. These role models ranged from accomplished social entrepreneurs, spiritual leaders, CEO’s, doctors, and more.

While the Role Models were impressive and thought provoking, they more provided a starting point for our conversations. In fact, I found the 450 yatris around me to be the true Role Models of my experience. They were the ones that pushed my thinking, and exposed me to many varying perspectives.

Biz Gyan Tree and Panel Discussions:

Every yatri (participant) was part of a 7-person team called a “cohort.” Together, 3 cohorts made a “group,” and each group had a focus area. Here were the 7 sectors of focus:

- Agriculture and Agro Business

- Healthcare

- Energy

- Education

- Water and Sanitation

- Manufacturing

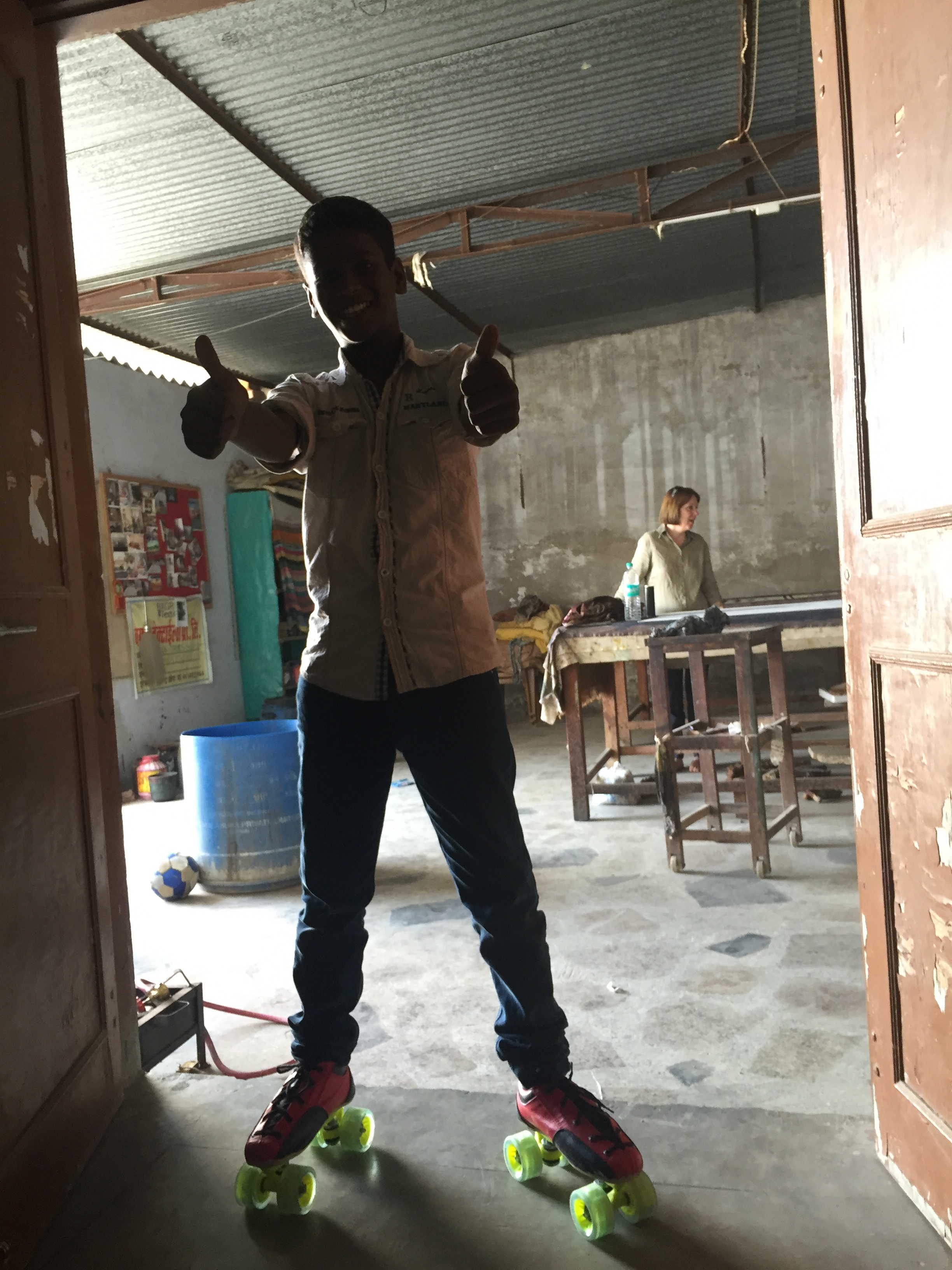

- Arts, Culture and Sports

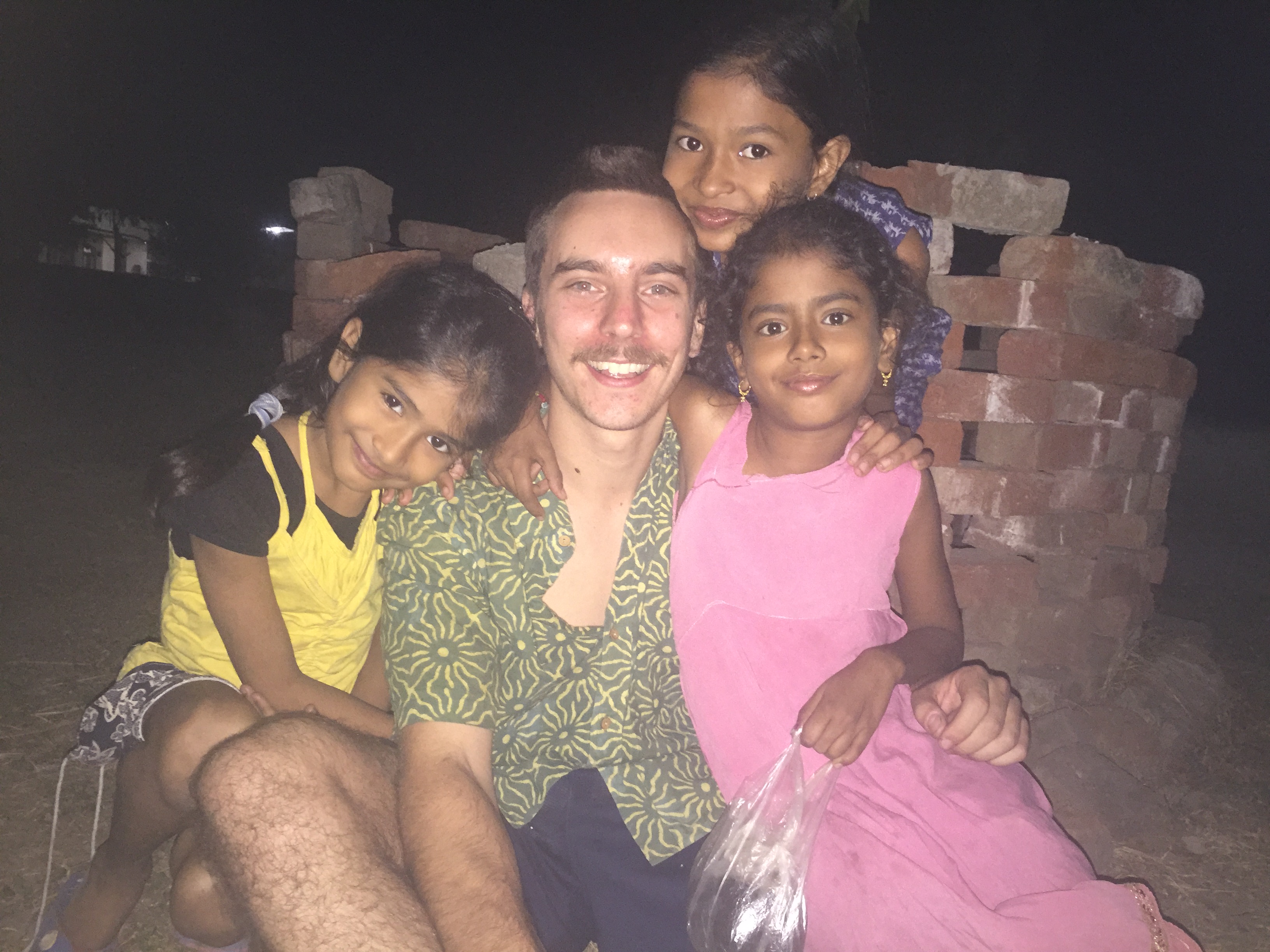

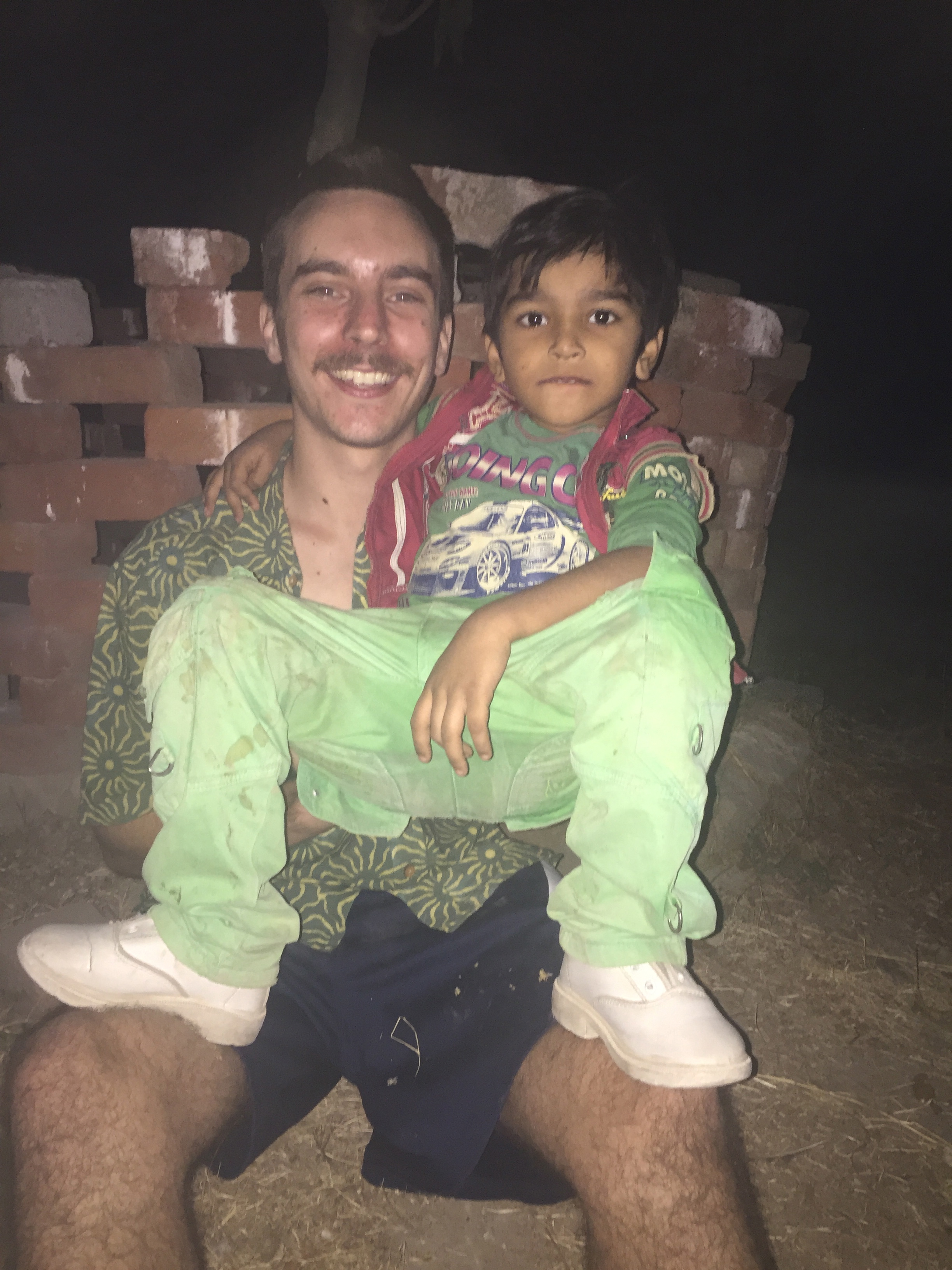

My group was assigned to the education vertical. Each group was responsible for preparing a business plan to be implemented in “middle India.” When we visited villages in Deoria, we had the opportunity to test how viable our plans were against the market. Finally, we had a Biz Gyan Tree competiton where each group pitched their ideas to Role Models and experienced professionals. A few winning groups were chosen to return to Deoira next month to put their ideas into practice.

We also had a number of panel discussions throughout the yatra, which varied in topic. Overall, these panel discussions were more casual than our Role Model speeches, and provided the opportunity for us yatris to ask questions and engage wih the panel.

Why we did it:

The founder of the yatra, Shashank Mani – who traveled with us most of the way – admitted that the journey isn’t supposed to be comfortable. In fact, it’s meant to be opposite. You’re supposed to get claustrophobic. You’re supposed to be disgusted, frustrated, and humbled. You intentionally sleep next to someone with the most radically different background than your own, and you’ll learn to respect them. You’re living in an environment where you’re bound to get sick, where your body will ultimately shut down, where you’re so tired you become a walking zombie. It’s all part of the master plan. It’s part of the yatra.

2015 commemorates the 100-year anniversary of Gandhi’s train journey around India. After retuning from South Africa, Gandhi wanted to see the “real” India; he wanted to experience the struggles of his Indian comrades, he wanted to see the rural lands that his affluent colleagues wouldn’t tread near. As such, Gandhi rode in 3rd class on the Indian Railways for three years, packed into tiny compartments, rubbing shoulders with lower castes, and witnessing India through the most authentic lens possible. Our yatra attempted to mimic this journey.

The aim of the Jagriti Yatra is to “build India through enterprise.” The mentality is that India, the largest developing economy in the world, will be built by its middle classes. The notion goes as follows: the rich have enough money, and the lowest economic tiers get enough attention from NGO’s and volunteer organizations, which leaves Middle India: 60% of the population, 750 million people, located mostly in rural areas – neglected, poor, and stagnant. The yatra aims to bring entrepreneurial innovation from the train back to these villages. It aims to create jobs for Middle India, and develop this growing country through a conscious strategy. The Jagriti Yatra “seeks to inspire a new generation that recognizes that the only way they can discover purpose and find meaning is by self-employment.” Entrepreneurship, or social entrepreneurship to be more precise, is at the heart of this mission.

What I learned

I’ve seen a lot, and I’m incredibly grateful as a result. At age 22, I’ve witnessed more than most people have the chance to see in a lifetime. I’ve been to 18 countries, and in the past six months I’ve managed to cover nearly all of India.

So, now what? People on the Yatra refer to the experience as L.B.Y., (life before Yatra) and L.A.Y. (life after Yatra). My L.A.Y. starts now, and I feel more motivated than ever.

The Yatra exposed me, not only to the plethora of issues that India faces, but the number of people that are affected as a result. In that recognition, I also see opportunity. To me, this seems like a rare and critical time for India, and the world for that matter. I’ve returned to Bagru with a new perspective. I see more change and development than I did before. I see a threatened community on the cusp of opportunity.I see people’s lives changing dramatically in the next ten years, but they don’t see it coming. I see a need for guidance. It is concerning and exciting. It is threatening and challenging.

Naturally, people tend to surround themselves with similar individuals: same hometown, field of study, personality types, or even political affiliation. On the yatra, I was surrounded by the most diverse community I’ve ever seen, but palpably motivated – for change, for challenge, for development. We all had a hunger, a yearning for something, anything, in terms of both individual growth in addition to Indian development.

I had countless conversations of eerily similar nature: a twenty-something who went to a prestigious university in India, in the UK, or U.S., who has been left unfulfilled. How can we collaborate to create something with impact? This was our constant mindset. I routinely felt in the presence of greatness, on the cusp of an unknown drive. After every person I met, I truly thought to myself: Wow, that person is interesting. That doesn’t happen everyday. You can’t buy it, and people search for that type of energetic culture and never find it.

If you are interested in learning more about the Jagriti Yatra, I recommend visiting their website or Facebook page. An American yatra alumnus, Patrick Dowd, founded a similar journey in the United States. You can read about it here.

The Yatra Files (4/4): Journal Entries

I wrote daily journals on train. In order to give you the most authentic version of my experience, I’ve copied excerpts below. I’m using the exact words I used in my journal in order to give you the best understanding of what I was seeing, thinking, and feeling at that very moment.

Note: These are just excerpts – not full entries.

Day 1:

The most intelligent people I’ve ever met surround me. Everywhere I turn I meet accomplished entrepreneurs, CEOs, medical engineers, PhD’s, patented innovators, etc. People are from all over India – all over the world. And people work in different places as well: India, U.S., Canada, Qatar, Dubai, the list goes on. I feel welcome. I don’t feel intimated by the success around me, but rather motivated. Like I belong.

Everyone is on the same playing field on the train. No matter if you come from a village, or a penthouse in Mumbai, we are all together. We’re all stacked 3 beds high, living on-top of each other, sharing the same hole for a toilet. This trip is the ultimate steamroller for equality and balance. We are one.

Day 2:

Christmas. I woke up on a train. You can’t hide here. Teeth brushing, sleeping, hanging out – there is no solitude. My evening was packed full of political conversations about ISIS, capitalism, Donald Trump and electoral systems. I love it, but some people seem too excited, like this is the best thing they’ve ever done. We’ll see.

Day 3:

Euphoria is the word that comes to mind. I feel passion and thrill, a type that I haven’t experienced since my first weeks in India. As though something epic is in the air. Our Role Model visit today wasn’t overly interesting – we went to a school that uses traditional music to educate their students, and also runs off solar energy.

Discussed the topic of marriage in India today. Still baffles me how most of these people will have their marriages arraigned. It is one thing that education will never change in India – love marriages simply aren’t the norm. Development doesn’t have tentacles everywhere – some things remain untouched.

Took my first “shower” today. I used a plastic water bottle to bathe… it was awesome. Classic. Bunch of shirtless Indians belting out songs in Hindi. Didn’t matter they weren’t real showers or the water was freezing. All different walks of life. Reminded me of camp. The train looks like a cabin now with underwear and wet towels hanging from bungee cords. Nobody is comfortable, but at least we all have that in common.

Day 4:

Fatigued and tired, but battling through. It is not even 8am and I’ve already had three cups of chai and breakfast. We are almost in Bangalore. An absolute mess brushing teeth this morning. 30 people trying to use one sink at the same time. We ran out of water before it was my turn.

We saw Shiri Shri Ravishankar (famous guru) speak about the “Art of Living.” Wasn’t my favorite visit, but I learned a lot about the business side of spirituality. He has a huge following. An educational experience to say the least.

Day 5:

The landscape is changing and so am I. Train is home; outside is just a placeholder for the time we spend on this moving vehicle.

The south is beautiful – I am in Tamil Nadu. Went to Aravind Eye care today – they run a great healthcare model that has given 4.5 million cataract surgeries in the past 4 years. The volume of patients they are seeing is simply impressive.

Their model is based on the honor system: if you are poor, you get free eye care, if you can afford some care, you get a subsidy, and if you are rich, you pay for it. The system works really well here, but I don’t see it working in the West. In India, people know their “place” in society, but in Western culture, there is less differentiation between social class. Caste obviously plays a role in this contrast.

Day 6:

Hot, humid, and sweaty. We spent the evening singing Hindi songs – very fun.

Day 7:

We move north. It’s a picturesque morning as we move our way to Vishakhapatnam: a glowing green on all the trees, shining from the sun’s reflection. You can see the dew on the every leaf this morning as the train goes on. The sun rising beyond the hills – it will be another hot day today. I could repeat this every morning if I could. I’m yearning to run here.

Day 8:

New Years Eve. My first, and probably last, New Years I’ll ever spend on a train. I’ll never forget it. We went to Gram Vikas is Orissa – my favorite Role Model to date. They provide sanitation projects (mainly toilets) to rural villages. We visited one village where they work, which was a nice experience. Reminded me of Bagru. I was shocked how the Indians were acting – many had never been to a village in their lives. They were more foreign than I. I felt comfortable talking to the people in that village, like I was in Bagru again. Simple living.

After our visit we went to a school where there was a massive dance party. I danced a lot. Indians are always ready for a dance party.

When I got back to the train I started vomiting. A lot. My first time getting sick in nearly seven months in India – my body can’t handle the oil from this food. It is rejecting it completely.

Living in carriage house at Union last year was definitely training for tonight. Spending New Years on a train with 450 youngsters, dancing and blasting music, while I was throwing up – brought me back to living in an animal house. Living in such a dirty and constantly loud environment last year prepared me well for this. Sometimes no matter how loud and annoying people get, you just have to streamline their enjoyment to lift up your own spirit. Patience is key.

Day 9

I’ve gotten used to the movement of the train. It helps me sleep. My jeans are dirty. I mean fucking dirty. I don’t have another pair of pants.

We’ve spent all day on the train. I am sick. With each passing day, the cleanliness, hygiene, and overall health of the train is decreasing. There seems to be a filth piling up on every object in this train; it is an “inescapable modality” as James Joyce would say.

I am becoming more intolerant of those around me. Small things tick me off. I desperately miss the structured, organized, and healthy lifestyle of my summers at home. I need protein – I feel frail. The singing around is ceaseless – I must learn to adapt and embrace it. Everything is getting under my skin, but I’m trying to find the beautiful chaos of it all that I know exists. It has stolen my heart before, and it will again.

Day 10:

Rajgir. The birthplace of Jainism and Buddhism. The history is incredible. We visited Nalanda University – a progressive type of school with a liberal arts model. Made me realize how far ahead the U.S. is in terms of university education models.

Eager for challenge. I don’t know what 2016 will bring, but I am committed to running a 50-mile race this year.

Day 11:

Deoria. A long delay this morning, but we made it. Today is the final day of our Biz Gyan Tree competition (business plan). We are trying to implement business models in this impoverished agricultural district. In contrast to Rajasthan, this place is lush and green – similar to Bagru, but different in its aesthetics.

Got my appetite back for the first time in three days. We had two hours to prepare our business pitch. I was elected CEO. It was a fun time. We made a good pitch – I don’t think we will win, but we came together as a team and got creative. That’s what matters.

At night we had a fun dance party. Everyone here seems happy the business plan competition is over – a more relaxed vibe.

Day 12:

We slept on the dirt floor of a school in Deoria last night. It was freezing, but my sleeping bag and winter hat saved me. I feel even closer to these people after sleeping alongside them in such a rogue environment. We literally kept each other warm last night.

Full day today on the train. Crazy how 24 hours on a train doesn’t even seem long to me right now. Just another sunrise, sunset…the way it goes.

Day 13:

Delhi – the nation’s capitol. We went to Gandhiji’s grave to pay homage to his journey that we are replicating 100 years later. A true inspiration, though a stubborn man (in an admirable sense). Though, it did end up getting him assassinated by another Hindu. A strange, sad story. An MLK-like figure here. Father of this country.

We sat in an auditorium this afternoon. I slept a lot. Pure exhaustion. My body is struggling with this food.

At night we went to Goonj, a great Role Model visit. They make women’s sanitation pads out of recycled fabric and other goods. It was an honest and blunt portrayal of Indian poverty.

The Role Model was originally inspired after he worked in Delhi with a man who collects dead bodies off the street for 200 rupees each. Heart-wrenching speech.

Day 14:

Back in Rajasthan [the state where Bagru is]. I feel home. Woke up this morning with a head-cold, but a jump in my step. The feeling I get in this desert is indescribable. People even commented that they could tell I was near Bagru because of how good of a mood I was in.

We went to Barefoot College – my second visit there. They have “solar mommas” from villages all over the world who come here to do solar engineering. Many can’t read or write, but they can make a solar panel. I saw the same women from South Africa that I had met three months ago. They are still at Barefoot making solar panels, and are excited to go back and “light up their village” in South Africa. I would use the word “inspiring,” though I learned that word can be misleading…we’re often inspired by something but don’t actually follow up on that feeling.

Nice to finally meet Bunker Roy, the founder of Barefoot College. I asked him a question in the Q+A about replicability – impressed with his answer. His model works. The success speaks for itself.

Day 15:

Final day. Everyone is dressed in formal Indian clothes. Looking good despite our poor hygiene. I feel like I’ve pressed pause on my life and it’s about to resume. A bit daunting, while also exciting. Trains make you think; naturally, you just stare out the window and your mind wanders. What a genius journey this has been.

Day 16:

Ready to get off the train – we’ve been delayed nearly 6 hours getting into Mumbai. Everyone is sick, but we’re still writing goodbye letters and diary entries. We’ve been transformed. A lifelong network. Lifelong friends. Onto the next one.

HEADING ON THE JAGRITI YATRA

Tomorrow I embark on yet another journey.

I have been selected to participate in the 2015 Jagriti Yatra – a 15-day train journey around India for young social entrepreneurs. Out of thousands of applicants, 350 Indians and 50 foreigners were selected as ‘Yatris’. I am lucky enough to have been selected as one of the foreign Yatri candidates. I want to thank my friend Julia Hotz who sent me the application months ago.

Essentially, the Jagriti Yatra brings together young, motivated people to change India’s future through enterprise. We come from all backgrounds – 60% of the participants are from rural villages in India. Some have never left their villages, others have never been to India. We are coming together to create something magical.

I will be living on a train for the next 15 days. It is the largest train journey in the world.

Their slogan is “Mahatma Ghandi discovered the nation in a train and so will you.”

Most days, the train stops in a new location where we hear a “role model” speak about social entrepreneurship. For example, the stop in Rajasthan is at Barefoot College where we get to meet the founder, Bunker Roy (TIMES 100 Most Influential People in the World). The rest of the role models range from CEOs of social enterprises, Indian scholars, etc. You can see the list of role models on the website. These stops are followed-up by workshops, discussions, etc.

The majority of the time is spent on the train with other young people who are passionate about social entrepreneurship. They encourage you to have a cup of chai with someone, use a whiteboard, and see what ideas we can come up with. Some of the most famous and successful entrepreneurs in India have participated in this program.

CHECK IT OUT: WWW.JAGRITIYATRA.COM

I’ll be journaling every day and taking down everything I learn. I return to Mumbai on January 8th, and fly back to Jaipur on the 9th. I’m sure I’ll have plenty to tell you after that.

Wishing you the happiest of holidays and a safe New Year to you and your families.

Best,

Davis

A Balancing Act

I used to have this theory of equilibrium: all people, no matter where they are from, come out even in life. Essentially, for every hardship one encounters, a balancing positive will arise. This was my way to justify anything I saw in life as ‘unfair’: death of a family member, children with cancer, homelessness, or rejection. As an adolescent I truly believed this formula worked – if you lose a loved one, you will meet another to love. If you were poor and hungry as a child, perhaps the strength gained from that experience transforms into a successful adulthood. It’s a naïve formula that I no longer believe in. Let me tell you why.

This world is far from balanced. Most of us can’t ‘balance’ work, play, and family. I surely can’t balance a checkbook; hell, the ‘balanced’ diet you’re following is probably protein or carb-heavy. More poignantly, there is an innate disparity – a lack of balance – between social classes here in India.

Our journey on the mini term directly introduced us to India’s multitude of faces. I realized slowly that, while I thought I really understood India, Bagru does not, and cannot, explain Indian culture as a whole. Truthfully, it barely scratches the surface of rural India, without even touching on the differences with the urban. I’m currently sitting in a café in Mumbai that feels worlds away from Bagru – even New Delhi for that matter.

Going back to balance. The best forms of government create balance. This is playing out perfectly in the American election cycle right now, where ‘inequality’ is one of the most commonly used words on the campaign trail (aside from “boots on the ground.” Yes, I’m talking to you Ben Carson). The roots of imbalance are vast, ranging from crony capitalism to corruption and, in India, caste. Stability and balance are essential for functionality between families, socioeconomic class and businesses, between religions, political parties, and ourselves. In addition, balance is a key indicator to quality of life. It’s no secret that Scandinavian countries have the lowest Gini coefficient, (measuring economic inequality) and also the highest quantifiable quality of life.

While wealth is a main contributor to this hypothesis of balance, I’m not only talking about economic inequality.

On our last night in Mumbai we went to the rooftop of the Four Seasons hotel for a goodbye drink. The Four Seasons is the nicest hotel in Mumbai in the center of the city. The setting was picturesque. We looked out on a beautiful orange sunset backlit the skyline before us, the sun dipping below the ocean horizon for as far as we could see. As my eyes wandered down however, I descended upon the slums directly below. As I sipped my drink, millions of people living off less than $4 a day were staring up at me. I was wondering what they were thinking.

Only days before, we were on a tour of Dharavi, one of the largest slums in the world – home to 1 million people, and the location of Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire. As I walked through the narrow alleyways of filth and gut-wrenching odors, I was fascinated by the organization and lifestyle of the slum, but less concerned with the poverty. After all, I’ve seen slums in Cape Town, South Africa before, and I’ve lived with amidst poverty for the past five months. What bothered me more was where I was going – after I left the slum.

I had seen the way the inhabitants of the slum were looking at me before; it is the same way our printers in Bagru look at our foreign clients or tourists passing by. It’s not a look of hatred or jealousy, but rather pride. It’s a look that says, “you couldn’t live here if you tried,” or “you wouldn’t understand what I’ve been through,” or “have fun at your hotel. I’ll still be here.”

From my experience, most poor people aren’t ashamed of what they have – they’re proud of themselves for persevering and succeeding with the cards they’ve been dealt. Now, that is an admirable quality.

There is a distanced relationship between the passerby and citizen, where respect must be earned, not given. I wanted to stand there in the Dharavi slum and tell them that I can do it. I want to live with you. But, at the end of the two-hour tour, we boarded our coach bus and went to Starbucks, shopped around a mall with Gucci and Rolex stores, and slept in our hotel with fresh linens.

I’ve found it amusing yet perplexing that I’ve been able to seamlessly float between the rich and poor of India. I’ve seen arguments in Bagru about purchasing a 5-cent pencil. I’ve even screamed about 2 cents with a rickshaw driver. I’ve legitimately fired a printer in Bagru who make less than $150 a month, and gone to malls in Mumbai that are no different from American luxury. I’ve felt comfortable in both circles. Now I’m having trouble deciding to which I really belong.

I feel more unbalanced than ever before, like a swinging pendulum that shifts every second. Union seems closer than ever, but miles apart.

If you were to ask me if I could pinpoint 1 skill since I’ve been here, what would it be? My answer would be this: if you were to drop me in any village in Rajasthan, India, I would have no problem walking around and making friends. I wouldn’t feel intimidated approaching a Chai stand with ten Indian men with fabric wrapped around their heads, shooting the shit in Hindi. It’s an intangible skill that I’ve developed, a certain second-hand nature of how-to-act and what-to-do. Yet, at the end of the day, what does this really get me?

On the contrary, if you were to drop me in any poor neighborhood in Chicago or Detroit, I would feel lost and foreign. I’ve found a sense of belonging in a very particular place in the world – a very specific place in India. Now, I’ve been on the other side of the swinging pendulum; in Mumbai, I’m just another dude.

I’m still trying to find the balance. So is India, and America, and each one of us.

Mini Term

Yesterday I finished a 3-week mini-term with a group of 16 Union students. To be honest, I currently writing from Mumbai where I find myself overcome with a deep sadness, a sadness that I haven’t felt since coming to India.

From a holistic lifestyle perspective, spending time with Union students was a treat. I honestly forgot what it felt like to be an American college kid again. In the past six months I’ve gone from doing keg stands and playing Edward 40-hands, (if you’re not a millennial, look it up) to spending time with my family and dog, to living in a rural Indian village, to getting in the best shape of my life, running the world’s highest marathon, to living comfortably in solitude, thriving in a new city, and expanding the definition of my home. My latest journey on the mini term might have been the best of all.

The first few days were incredibly frustrating. As I described in “Fitting In,” I have developed a liberating belonging in India. The streets don’t scare me, but rather invite me to explore. As such, when 16 Americans arrived in Delhi and ventured out for food the first night, only to return minutes later and order room service, I was a bit befuddled. I quickly realized that my five months of “just do it” mentality, and understanding of the small cultural nuances of a foreign culture couldn’t be adopted in a few short days. But, as time went on, I realized I couldn’t blame them (sorry Julia, Hannah, Jessica etc.). I was the same guy not too long ago, deeply afraid of purchasing a banana from a fruit stand in Bagru. And just like I did, the students on the trip grew immensely with each passing day, learning and exploring India, becoming ever more accustomed to the poverty and chaos around them.

It was also nice to have intellectual conversations with other people than myself. Finally I had the opportunity to delve into issues I’ve been grappling with for months, and seeing others go through the same process made me reflect on my own experiences thus far. It was also nice to kick back and have a few drinks and have fun. Good, carefree fun with friends is perhaps the greatest thing in the world. Thank you, friends, for a fantastic time on the trip.

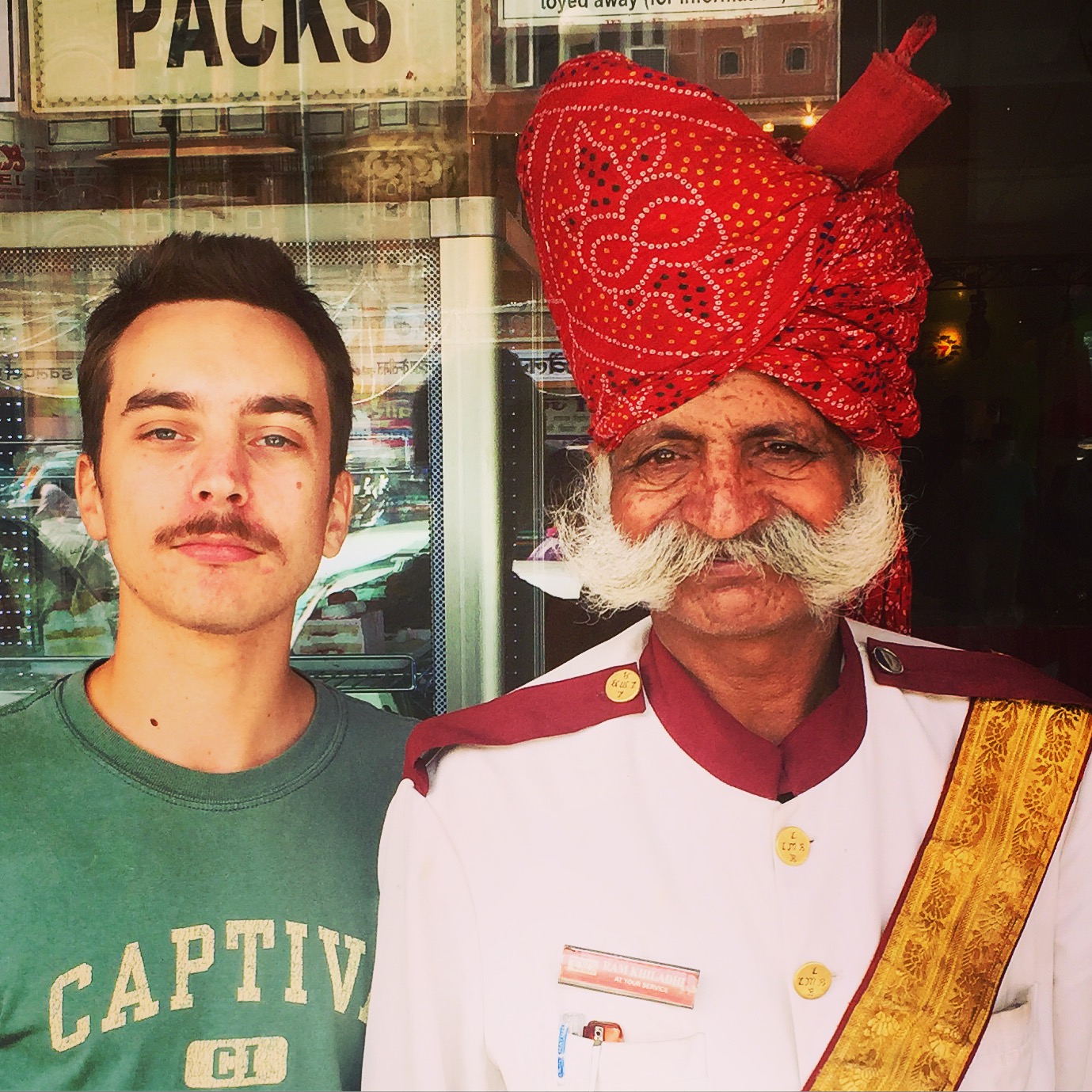

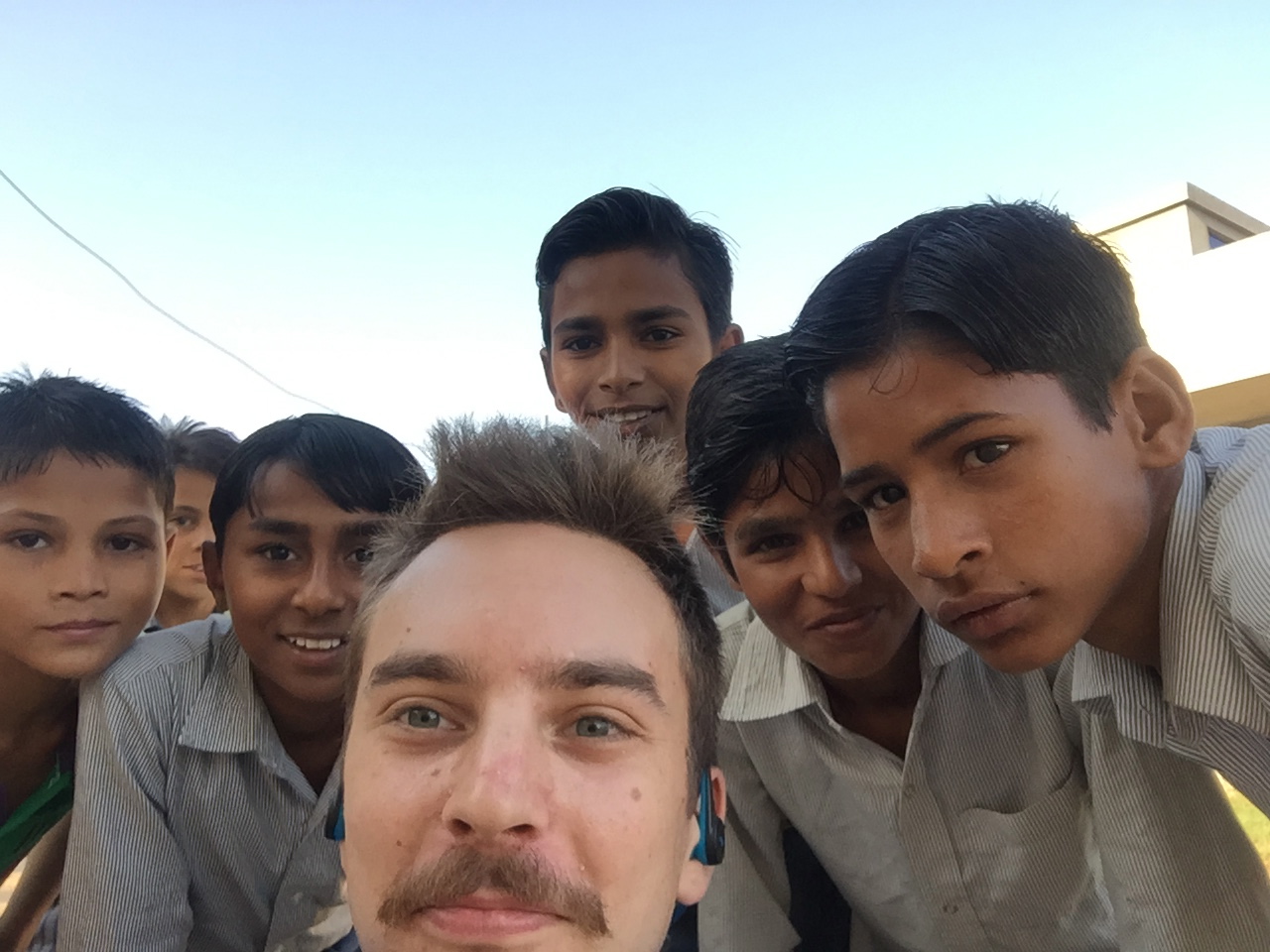

As the trip went progressed, I realized how far I’d strayed from the person I was back at Union. As the trip developed people kept commenting that I was transitioning from “Indian Davis” back to “American Davis” in my dress, appearance, language and behaviors. I even shaved my moustache. I’m not sure if I ever explained the reason for the stash – but there is a saying in Hindi, “Mooch Nahi, Tookuch Nahi” which translates to “Without a moustache, you are nothing.” I grew my moustache to gain respect in Bagru (and yeah, because I’m 22 and living in India). So, Davis is now clean-shaven. You’re welcome to all those who have requested to bring out the razor.

To be honest, I’m no professional when it comes to India. It the grand scheme of things, I still know nothing. I have way more questions than I’ll ever have answers. For better or worse, I think I’m just “Davis” and don’t need a country tagline.

Nonetheless, spending time with my peers made me understand just how different my life has been, and what the implications of are. I made amazing new friends that have changed my perspective on returning to India next year. While I am free and happy here – I miss my family and friends back home. Life is going by without me, and I truly feel that way now. I watched every student pack and leave for the airport, talk about what their first meal home would be, what their New Years plans are, and how they can’t wait to see their boyfriends/girlfriends. I’m still here. My brother’s engagement party last weekend, Christmas Eve, ski trips and family dinners. It’s all going by. Feeling a bit stuck, yet, this is what I signed up for. I find beauty in small moments, like walking outside and being overwhelmed by noise and color, or screaming at the top of my lungs on a beach run. Freedom.

Pushkar Mela 2015

I recently went to the Pushkar Camel Festival. Pushkar is a small town in Rajasthan, about 2 hours from Bagru.

Pushkar is a very holy place for Hindus. There is a small lake in Pushakar, which is said to be made from the tears of Lord Shiva’s wife after he died. Additionally, Pushkar is home to one of the only Brahma temples in the world. Brahma is known as “the creator” in Hinduism – part of the Holy trinity in Hinduism.

I know it’s easy to get lost in the names and Gods of Hinduism, so I’ll spare the complexity by saying this in laymen terms: Pushkar is a very, very holy place.

For hundreds of years, every November, Pushkar has been a site for camel and cattle traders to assemble to buy/sell their livestock. In that sense, not much has changed; many of the camel tradesmen have no relation to the “festival” that is advertised for the many tourists in India. For the camel traders, there are no set dates, but as the November days progress, hundreds of thousands of camel traders arrive from all over India. Alongside this special occasion, there hundreds of thousands of tourists who come to watch this ordeal, see the camels, and enjoy the “fair” events, i.e. an amusement park at night and different cultural dances.

My first reaction when arriving to Pushkar was that the fair wasn’t really for “me” – as a tourist, I was just an observer of the real event, where the camels were being traded. For example, although there were many shops targeting tourists, they were greatly outnumbered by shops for the camel traders; here, traders could buy camel saddles, ropes, farming tools, etc. I felt as though I was walking through the world’s biggest marketplace for ‘camel people.’ The most refreshing part of this was that nobody was approaching you to buy anything or haggling you. I was just a ghost wandering in the sand dunes, observing a different world, unbothered and unseen.

Pushkar is a very small place that gets flooded with people for the month of November for the camel fair. There’s only about 12,000 year-round residents – half the size of Bagru! But, throughout the year, devout Hindus visit Pushkar to visit the Brahma temple and bathe in the lake. Even though the water is murky and littered, you can always find people stripping down and wading in the holy water.

So, what can you learn from this? I found Pushkar to be fascinating for a very distinct reason: coexistence. During the camel fair, there are three specific groups of people in the town, living together in a chaotic harmony.

- The camel traders and their families

- Religious Hindus visiting Pushkar for the temple and lake

- Tourists, like myself.

Coming from a religious village like Bagru, I felt comfortable among groups 2 and 3. Since I’ve learned a lot about Hinduism and feel comfortable in Hindu temples, I could personally even feel a palpable spirituality in the holy Brahma temple.

With that said, I am the only foreigner in Bagru; I’m not used to seeing thousands of white people walking amidst ‘traditional’ Indians from Rajasthan. Then, to add the whole camel people to the equation, (one might call them nomads) was a beautiful cultural clash.

I’ve been trying to equate my experience at the Pushkar fair to something I’ve seen in America. The truth is, nothing like it exists – not because of the lack of camels, but due to the void of cultural acceptance.

In Pushkar, nobody seemed to mind what your business was. The streets were filled with half-naked gurus, hippie stoners from Israel, National Geographic photographers, camels, horses, and farmers who clearly hadn’t bathed in weeks. Nobody cared.

I can only imagine the political fallout or potential for violence this type of scenario would pose back home. Imagine a gathering with rich elites from New England, some ‘thugs’ from Oakland, and a community of Amish. And, let’s say it took place in a redneck town Alabama. Seriously, what the hell would happen?

Obviously this is hypothetical, but I couldn’t help but notice how invisible I felt in Pushkar, despite my utter contrast to those around me. It was refreshing.

A look through my eyes

Today, I am Thankful

I was lucky enough to spend thanksgiving with a small group of ex-pats in Jaipur. I was craving some turkey, but more importantly, just some company to share some laughs on a holiday that celebrates friends, family, and thanksgivings. I called up a friend in Jaipur and organized a small dinner with two British guys, and three girls respectively from Zimbabwe, Spain, and Columbia. It was an educated and intellectual crowd, so everyone knew what thanksgiving was and was happy to celebrate with me. No Turkey here, but we managed to get a blend of Chinese/Indian food.

Notably, this was one of my first instances in India that where I was spending an extended period of time without any Indians. This was a group of people, all of whom work and live in Jaipur, and had keen observations of Indian culture to share. Most of our conversations surrounded differences in gender equality, censorship in the media, and talking about the difference between touring – and living – in a country like India.

During our meal, true to thanksgiving form, we each shared what we were thankful for on this special day. I was first to go, and explained that I was thankful to have celebrated a thanksgiving so far from home; for a holiday that rejoices among family, I felt delighted to be able to maintain a tradition so far away from home. Everyone appreciated the sentiment, and continued around the table.

There was short pause. Everyone was looking at one another, waiting for the next person to share their ‘thanks.’ It seemed there was an elephant in the room, as though they were all thinking the same thing – and they were.

Finally, my friend Alex blurted it out: “How about the dead bodies we’ve all seen on the side of the road? I’m thankful to have this” – he gestured with his arms to the plate of food in front of him, his friends around the table, and a comfortable apartment.

I felt disgusted with myself – it hadn’t even crossed my mind. I’m living amongst grotesque poverty every day here, and I hadn’t spent a second thinking about how fortunate I am.

I had even seen a dead body (or D.B. as we sometimes use as a euphemism) on the street just the day before. It’s something I’ve gotten used to at this point, but was surprised by my lack of acknowledgement.

In past thanksgivings, I used to actually feel bad about how easy I had it, growing up in an affluent community and welcoming home. I remember wanting to give back my first iPod that my parents gave me for my birthday. I knew many people couldn’t afford one. Even with homeless people back home in Boston – I used to glare at them, pouring my heart out, and feeling angry at the inequality.

Now, in India, I’ll be driving under a bridge where homeless people are sleeping, and there will be a government official walking around checking pulses.

You can read my post below on “Becoming Numb to Poverty,” which might help explain a bit of this ignorance on my behalf.

This topic of poverty opened up another conversation about welfare in India. To put it bluntly, there is no safety net here – no social welfare, security, or people to call when you hit rock bottom. The infrastructure that is in place – the homeless shelters and medical clinics – are overrun and outdated.

India is a lawless country.

What do I mean? You can do whatever you want, wherever you want. Nothing seems to be ‘illegal’ – if you want to drink and do drugs, go ahead. Nobody will stop you. If you need to pee, the earth is your toilet (literally anywhere. This goes for trash as well). If you want to steal, don’t get caught. There are no formal queues or lines, no rules of the road, and certainly no limit to how many people can ride in a car, tuk tuk, or on a motorcycle. Anything goes. There’s a saying in Hindi, “sub kuch milega” which means, “anything is available.” If you have the money, you can buy anything – an illicit commodity, a high score on a test, someone’s freedom, or the shirt off their back. Everything is for sale and up for negotiation – a black market for life. It’s exciting and fun as a visitor, but incredibly concerning and daunting when you consider the implications.

Here’s the point: many Indians will argue that if you end up dead on the side of the road, it’s your own issue. There is no ‘ownership’ as a society. If you’re sick, it’s up to you to pay the hospital bill. If you can’t – well, as they say…“See-ya.” The dog-eat-dog mentality is something I used to despise as a liberal American. And I still do. But, with that said, the shear magnitude of these issues is too overwhelming. People are tired of the endless cyclicality of money spent and wasted. Even for people who want to help, the fundraising and non-profit sectors in India are filled with corruption and payoffs.

Today, I’m thankful for what I have and the welfare I have as an American citizen. I’m also more perplexed as to how address these issues in India, particularly as I become more and more comfortable living in a society that disregards many in its population as a lost cause.

Blending In

As I was walking down one of the busiest streets in Jaipur yesterday, a rickshaw (tuk-tuk) driver pulled to the side of the road – a common, daily occurrence. It happens wherever I go, at all times of the day. As a white person in India, I am constantly asked if I need a ride anywhere, want a tour around the city, or a number of other services. I’ve gotten used to brushing these people off without much thought, and carrying on my way.

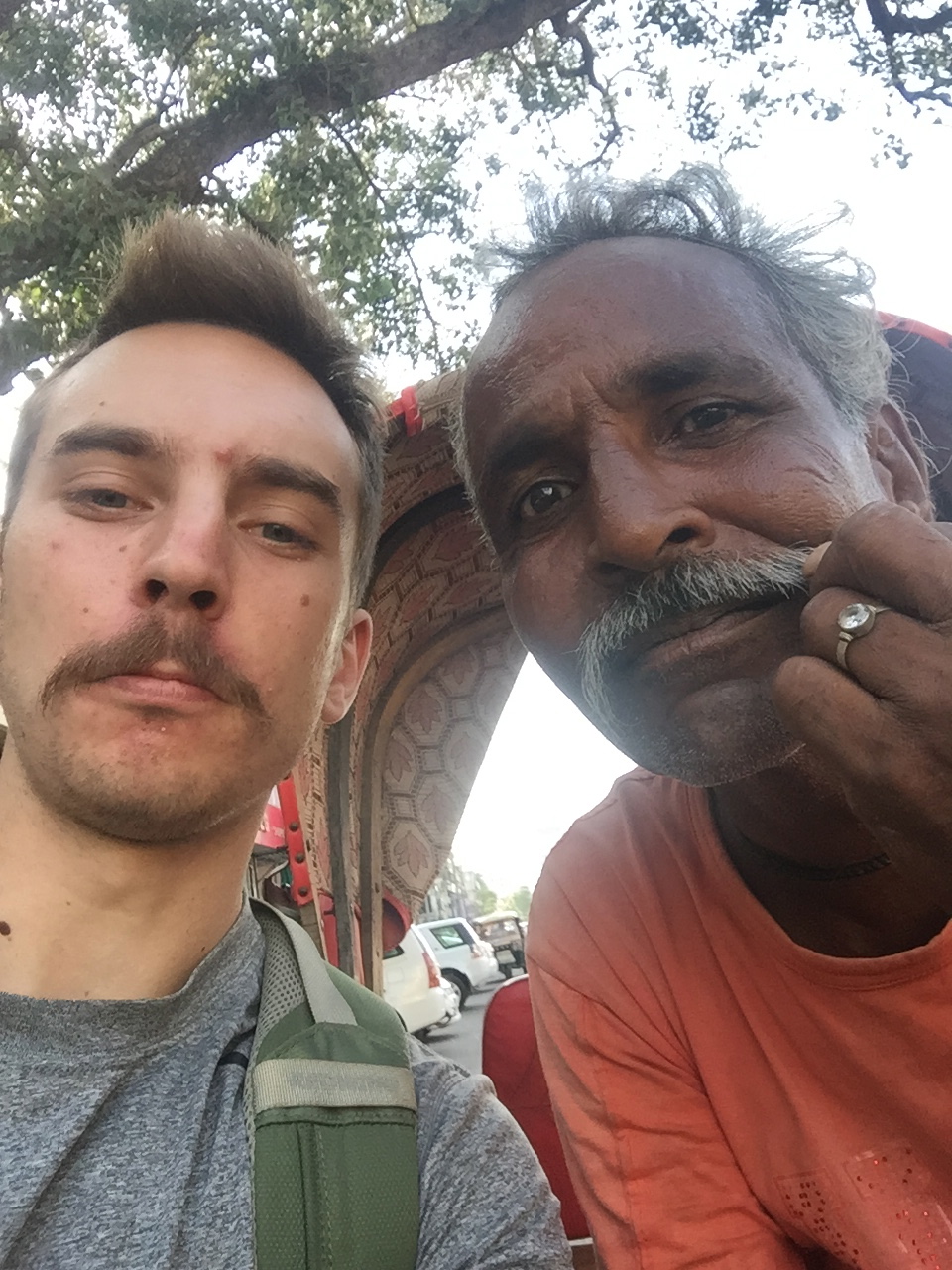

So when the rickshaw driver first pulled over next me, I gestured with my hand that I wasn’t interested in a ride and kept walking, ignoring what he was saying. After several more attempts to catch my attention, I finally turned my head to hear what he had to say. In a perplexed curiosity, the man said to me:

“My friend, you look Indian. How you become this?”

I was incredibly shocked. The man wasn’t asking if I wanted a ride, wasn’t haggling me for anything. He simply was impressed and interested by my demeanor. I was honored an excited – wow! After living in India for four months, I’ve officially embedded myself into the deep crevices of this culture. It’s a hard-earned respect.

Admittedly, one could attribute this man’s curiosity to my mighty mustache, or even the Bagru block-printed shirt I was wearing. But, I don’t think that explains it all.

He said I “looked” Indian, which of course can be attributed to my appearance. After all, I’m a short guy, and I’ve lost all my muscle mass; now, I’m a frail vegetarian whose body mimics the Indians I live amongst.

However, that doesn’t answer the man’s question: “How did you become this?” The man wasn’t just commenting on what I looked like. He was commenting on how I acted.

There is a certain behavior, a flow, a chaos, which I now deeply understand and feel part of. There’s a level of comfort that is required in order to navigate India, its people, and streets – the sounds and color – to fully recognize that everyone is a piece of the puzzle. Together, the masses of people, animals, trash and street vendors – we all make the ‘beauty’ that people come to India to see. It’s for this reason that I never recommend seeing the numerous temples and forts in Jaipur, (sorry) but instead walk down the streets. Try, at least, to be a part of the tumultuous flow – don’t just take pictures and email home about it.

I’ve developed a swagger. This isn’t any type of swagger I can relate to anything back home. It’s not the type of swagger that Kanye and Justin Bieber have; it’s a swagger that isn’t learned – only lived.

My swagger blends in with the dirt and dust that covers each and every Indian street; it makes me disappear into the backdrop of the hustling scene. I am proud of this swagger, as it cannot be taught. It’s developed through an astute observation of cultural nuances, small things that are unspoken and unrealized by the local people.

Now, I not only “look” Indian, but I feel it as well.