Fu Baoshi belongs to a fascinating period of Chinese history that saw continual struggle, widespread devastation, and profound identity loss. As a child, Fu witnessed the collapse of Chinese Imperialism and endured its repercussions. What he saw was factionalism during the Warlord era, Communist rebellion, foreign occupation, and finally the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. Along the way, China experienced drastic changes, which subsequently placed heavy burdens on the shoulders of its people. Under the Communist movement, feudalism became collectivization, the bourgeoisie became enemies of the greater public, and students of traditional Chinese culture faced immense scrutiny and ridicule. Fu Baoshi exists for the most part as an exception however, embodying a unique style that features a blend of traditional Chinese values with modern progression.

Under the Communist Party in China, culture started to look to the present and future and began to divert away from traditionalism. At Mao Zedong’s Yan’an talks, the art of the future was outlined. Mao discouraged the practice of traditional Chinese art and placed emphasis upon the adoption of socialist realism and how it should propagate and advance Communist ideals by exposing those that oppress the common man. Following this forum, students of traditional culture faced immense downward pressure. Although Fu Baoshi had studied the traditional values of Chinese art, and studied abroad in Japan where he drew a lot of Western influence, his work developed a distinct style that coupled tradition with advancement. Julia Andrews from Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1947-1949, would describe his individual methodology as either revolutionary realism or revolutionary romanticism. This unique style carries profound importance in the context of Fu’s life because it allowed for some adherence to traditional Chinese culture to stay alive and be maintained in the face of what was essentially a Communist overhaul of Chinese culture.

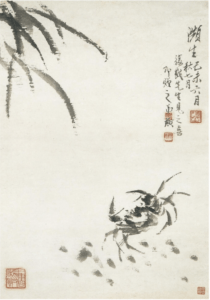

Fu Baoshi, Gottwaldov, Czechoslovakia, Album leaf; ink and color on paper, 1957