The exhibition will display the variety of Zhan Wang’s stainless steel sculptures and installations. Zhan Wang is a sculptor whom was born in 1963 in Beijing, China. Although throughout his successful career he has the opportunity to hold exhibitions in multiple other countries, Wang was artistically formed in China. His work is critical in nature and considered as part of the surrealism movement. The Surrealism movement in both art and culture seeks to reunite conscious and unconscious realms of experience so completely that the world of dream and fantasy can be joined to the everyday rational world in “an absolute reality, a surreality (The Surrealist Manifesto, 1924).” Wang’s critical pieces particularly center around decisions taken by the Chinese government while in his childhood and young adulthood. The exhibition will display the variety of Zhan Wang’s stainless steel sculptures and installations. It will feature an Urban Landscape installation, multiple sculptures including some from Wang’s Artificial Rock series and pictures of other pieces not present at the exhibition. Although Zhan Wang’s stainless steel pieces may all use the same medium, they represent many different critiques. The exhibition will attempt to give Zhan Wang’s distinct critiques in the medium of stainless steel a voice and home.

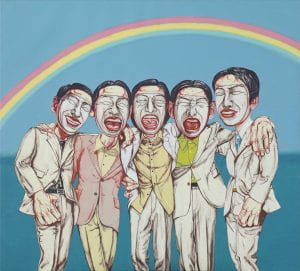

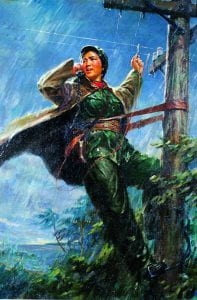

The reseason behind the specific medium selection is the originality and creativity in stainless steel sculpture and installation. Additionally, although Zhan Wang has pieces and installations across a variety of mediums, stainless steel is one of his most used. Many of his pieces in the medium have obtain high levels of fame such that stainless steel pieces have become a symbol of Wang’s work. This medium was acquired however, as the surrealism style associated with such pieces. His first significant works were traditional in nature, however, in 1990 Wang began experimenting with surrealism.

Wang’s first internationally recognized surrealistic series, the “Mao Suit” series, was first exhibited in 1994 and consisted of a composition composed of a variety of Mao style suits which had been solidified and posed in different ways. In 1995, his first internationally recognized stainless steel series was first exhibited, “Artificial Rocks”. Since then, the vast majority of Wang’s internationally recognized pieces, series or installations have been in the medium of stainless steel.

With the exhibit, I intend to highlight such pieces as a representation of Wang’s critiques of China, while detailing the differences between the pieces, series and installations in the medium.

Bibliography:

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Surrealism.” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 4, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/art/Surrealism.

Central Academy of Fine Arts. “RTSM | ZHAN Wang: It was already the doomsday, but I’m back to reality again.”. 2020. https://www.cafa.com.cn/en/News/details/8330204.

Wang, Alice. “Zhan Wang: Master Sculptor”. ARTZINE, A Chinese Contemporary Art Portal. 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20120310022556/http://new.artzinechina.com/display.php?a=200

the constraints of traditional Chinese painting and to experiment with new mediums and forms. It is a reflection of

the constraints of traditional Chinese painting and to experiment with new mediums and forms. It is a reflection of