In a line of works titled “Tobacco Project” Xu Bing symbolized humanity’s relationship with tobacco across art works including a book of tobacco slogans printed on tobacco leaves. This specific installation is a mock- tiger rug made of over half a million ‘1st Class’ brand cigarettes, carpet, and adhesive, and Xu Bing named it accordingly “1st Class”. 40 feet long and 15 feet wide, “1st Class’ is a larger than life tiger skin symbolizing “human prowess: it confirms our superiority by transforming one of nature’s fiercest predators into a lifeless skin beneath our feet.” (Ravenal, 2011) The oversized quality of the skin is no coincidence, as Xu Bing aims to invoke a slightly remorseful self-reflection. The size also doubles as a way to make one artwork into two: a massive collection of cigarettes and separately an oversized tiger rug, and the oversized tiger could additionally signify an especially dangerous or threatening animal. As a tiger rug is associated with “luxury, status, and domination” Xu Bing forces the viewer to think about the correlation between these traits and humanity’s relationship with smoking cigarettes. Ravenal writes “The beauty of the tiger-skin pattern, its allusions to the dangerous thrill of the hunt, and the uncanny allure of the massive display of cigarettes ironically glamorize the addictive pull and risks of smoking.” (Ravenal, 2011) The monochromaticity of the tiger is clearly not made to look realistic, but it is rather an artistic decision to switch the oranges and blacks of normal tiger skin to white and orange (with orange stripes over a white background, keeping the color scheme as that of the cigarettes). However, from other viewpoints some of the tiger skin looks like a darker brown color, and this is because from standing on the other side you can see down the end of the cigarette, creating a darker sort of stippled look. This may emulate two different views of or opinions on cigarettes; those who enjoy them for the taste and/or feeling, and those who are suffering from addiction or physical health problems manifested from smoking.

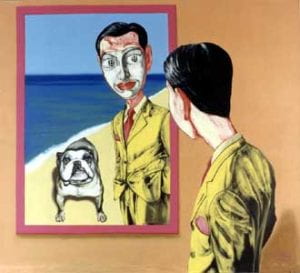

This is Mask Series No.26, an oil on canvas created in 1995 by Zeng Fanzhi. We are shown two happy figures, a man and his dog. The observer is situated behind the man in the work, almost as if we are looking over his shoulder and getting a glimpse into his life. This man is looking into a mirror that shows a realistic reflection of himself and a dog, however the dog is not next to him in real life. His reflection is on a beach elsewhere. The most significant aspect of the painting is the mask on his face in the mirror.

This is Mask Series No.26, an oil on canvas created in 1995 by Zeng Fanzhi. We are shown two happy figures, a man and his dog. The observer is situated behind the man in the work, almost as if we are looking over his shoulder and getting a glimpse into his life. This man is looking into a mirror that shows a realistic reflection of himself and a dog, however the dog is not next to him in real life. His reflection is on a beach elsewhere. The most significant aspect of the painting is the mask on his face in the mirror.