Zeng Fanzhi is a component of Chinas dynamic history, creating artwork serving as a lens into understanding the complex social and economic factors of China’s development. Over the course of his career, Fanzhi expresses realism (depicting the world how it actually is without sugarcoating), expressionism (a focus on emotions and personal perspectives), and lately abstract works (creative and unique settings very different from our physical world). Fanzhi is best known for his rejection of Socialist Realism, something which had been very popular during the Cultural Revolution. Socialist Realism was a method of promoting socialism and communism by creating works that were uplifting and inspiring. Zeng has clarified that his theme is the agony of being human.

The range of works that I am interested in exploring are his mask series, and his abstract works series tied together into one exposition. Key themes that I want to explore are identity and symbolism. The reason why I really enjoy Zeng Fanzhi’s works and why I was initially drawn to him is his unique talent mixed with rich symbolism. In the past I have explored body language and symbolism, and also smartphones with their impact on modern society. The symbolism of the masks and the changing societal mindsets parallel with topics I am interested in which make me very excited to create this exposition.

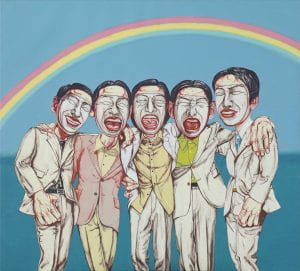

Others will gain important value as they learn about Chinese art in 20th and 21st century through the works of Zeng Fanzhi. His technical expertise using color, line, and form are great ways to springboard into symbolism. The Mask series paintings that I will include are Mask Series #13 (1994), #8 (1997), #6 (1998), and The Last Supper (2001). For example, #8 displays a group of men with exaggerated masks that depict them weeping and laughing at the same time, which is an interesting dynamic between emotions and identity. I think that the monochrome masks probe the tendency of Chinese citizens to hide feelings and emotions, leading to a sense of isolation. Fanzhi himself had feelings of isolation in 1994 when he entered Beijing, knowing no one. The others touch upon the same superficiality, as well as the intersectionality between the economy and sociology/relationships. I think that viewers will have a lasting impression and have a better idea of China after seeing this artwork because our minds are hardwired to respond to emotions and contextual cues, which the masks are a goldmine for.

The abstract work I chose is “Bodhidharma, Still There” 2015. It uses vivid greens, blues, yellows, pinks, and purples. I sense a feeling of movement, and is eerily similar to a dark scary forest. We are situated in the dense tangles of overgrown bushes and thorns, and we are essentially at the edge between Western abstraction and Classical Chinese Landscape Art. Zeng Fanzhi has put a new twist on ancient traditions. You could say Zeng Fanzhi went back to our roots, while at the same time going beyond them.

Works cited:

——–

Images

“Work of the Week: Zeng Fanzhi, ‘mask: Rainbow’ (1997).” ArtReview, artreview.com/work-of-the-week-zeng-fanzhi-mask-rainbow-1997/. Accessed 13 May 2023.

“Zeng Fanzhi – Evening & Day Editions New York Tuesday, April 23, 2019.” Phillips, www.phillips.com/detail/zeng-fanzhi/NY030119/325. Accessed 13 May 2023.

Zeng, Fanzhi. “Fanzhi Zeng: Bodhidharma, Still There, 2015.” Art Basel, 1 Jan. 1970, www.artbasel.com/catalog/artwork/33449/Fanzhi-Zeng-Bodhidharma-Still-There.

——-

Zeng, Fanzhi, Gladys Chung, Crystal Ming, Tiantian Feng, Fabrice Hergott, David Anfam, and Gustav Mahler. Zeng Fanzhi. Zürich: Hauser et Wirth Publishers, 2018.

Zeng Fanzhi : Catalogue Raisonn Volume I. Place of publication not identified: Skira, 2017.