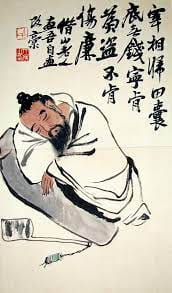

Qi Baishi, Stealing the Wine Vat, before 1957. Ink and wash painting. (Smithsonian)

Stealing the Wine Vat is a painting by Qi Baishi and he used ink and wash painting. The image Baishi painted is very simple; a man is sleeping on a wine vat and has dropped his ladle. The painting is organized such that the image is in the bottom left and there is writing at the top right of the painting. The painting has no setting, and the scene is in stasis because the man appears to be deep in sleep. The relationship between the painting and the viewer is a comical one because the story that is depicted is a well-known comedic story in Ancient China. The image is 35.9 x 25.8 cm which is pretty small showing that the image may not be of a grand event, but instead a normal moment in time. The proportions of the painting are also true to life because the man doesn’t look much bigger than the vat of wine or ladle. The painting references a scene from a story in Chinese history where an official named Bi Zhuo, “was so drunk that he stumbled into a neighbor’s house and continued to drink from an urn of wine. Inebriated, he fell asleep next to it.” (Smithsonian: 1) The characteristics of the painting follow Qi’s style of playfulness and realism in art. Many of Qi’s works were designed to entertain the viewer with the whimsical side of art. Rather than making art about controversial or heavy topics Qi’s art inspired lightheartedness in the viewer. The realism in this painting contributes to this theme as well because Qi was amused by this story so he decided to tell the story as close to his imagination of it as possible. One of the reasons Qi was so successful is due to his accurate portrayal of events that many people witness because they relate easily to his style and point of view.

References:

“Home.” n.d. YouTube. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://asia.si.edu/object/F1998.67/.