There has been, for years now, clamoring in political and economic circles to raise the government-mandated minimum wage to $15/hour.

Now, this sounds fantastic on paper. After all, who wouldn’t want to make $15 an hour?

Yet, there’s a simple problem with the $15 minimum wage: raising the minimum wage only raises the cost of living.

Think about it in basic terms. I’ve used my family’s pizzeria business before as an example, and I’ll do so again here.

Currently, I make $10.40/hour. That is, after all, the current New York State Minimum Wage. My family’s pizza business employs, let’s say, 10 workers. All 10 of these workers make minimum wage. Let’s say each person works 25 hours a week. That is to say that, per week, the business pays $2,600/week in wages.

($10.40/hour) x (25 hours/week)= $260/worker ———- ($260) x (10 workers) = $2600/week

Now let’s say, all of a sudden, the minimum wage jumps to $12.50/hour, as it is scheduled to do by the end of 2020. Now, the business must pay $3,125/week in wages.

($12.50/hour) x (25 hours/week) = $312.50/worker ———- (312.50) x (10 workers) = $3125/week

Now, this is fantastic for the individual worker. Working the same number of hours, and doing the same work, they see their weekly income rise by over $50.

Yet, for the small business owner, this is unfortunate. The small business owner now must come up with an additional $500+ to pay their employees. That money doesn’t simply fall out of the sky, or off of a tree. How do they reckon with this? They take the only reasonable avenue available to them. The business owner passes the cost onto the consumer. They raise their prices.

Now, our employee has to pay $8.00 for a cheese pizza when it used to cost $6.00. They have to pay $12.00 to see a movie at a local theatre, when it used to cost $9.00.

Soon enough, the $50 raise they got as a result of a rising minimum wage is gone. It evaporates into thin air.

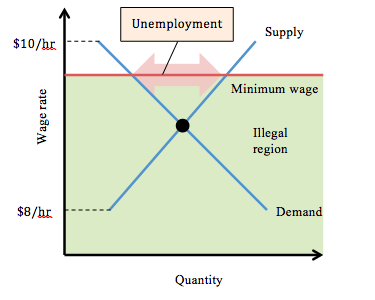

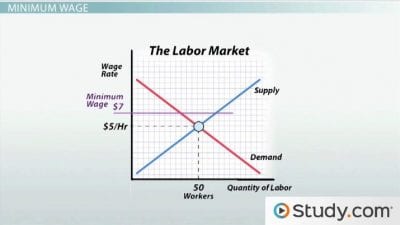

I attached some pretty rudimentary graphs below to try to help illustrate.