Sedimentary rocks are derived from the erosion of all rock types: igneous, metamorphic, and other sedimentary. Materials are eroded, transported as particles or as dissolved chemical species in water. These materials are eventually deposited as the particulates settle out (clastic rocks, e.g., sandstone), or as dissolved chemicals precipitate from solution (chemical sediments, e.g., limestone). Grain size can vary widely, as can mineralogy and color. Fundamentally, however, sedimentary rocks are classified according to what makes up most of each one.

Typical appearance of clastic rocks

Shale

No grains are visible, or perhaps only a few muscovite crystals seen on bedding surfaces. Shales are mostly made of clay, a diverse group of tiny mica-like minerals. Some shales are very soft and fall apart in water, others can be quite hard. Shale is the most common sedimentary rock type on Earth. In general, they feel smooth when scraped by a fingernail. Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

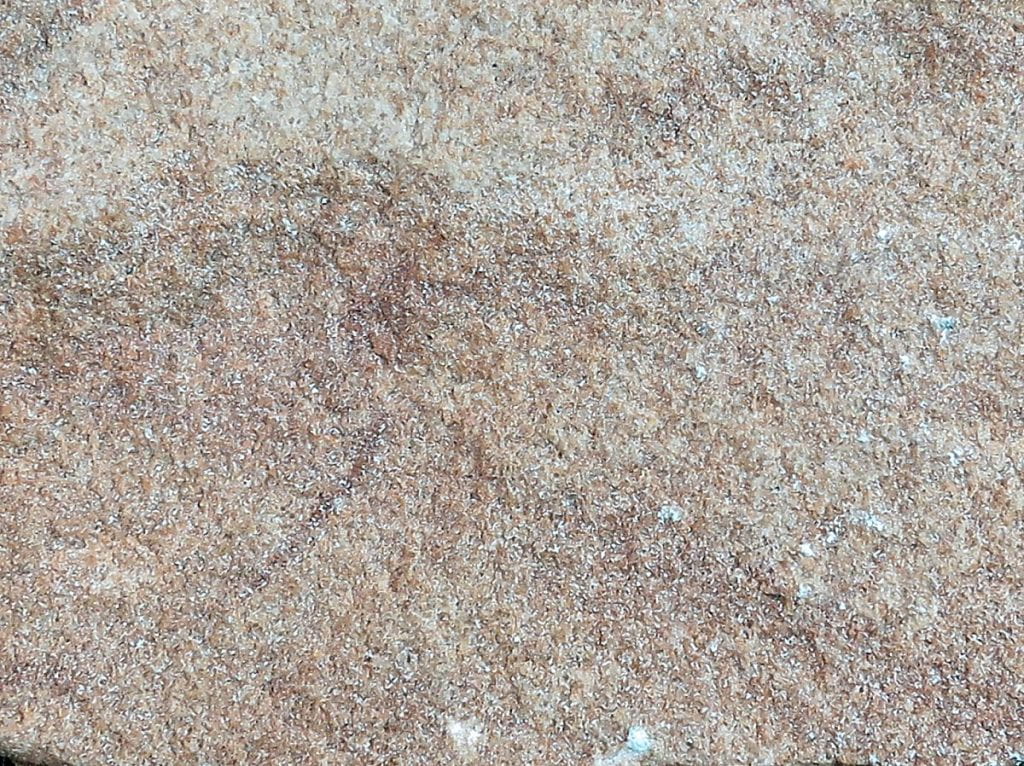

Siltstone

Mineral grains are barely visible with a hand lens or low power microscope. Grains are too small to identify except as indicated by dark or light color. Quartz, feldspars, and clays are the most common. Feels rough when scraped by a fingernail, like an unglazed flowerpot. Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

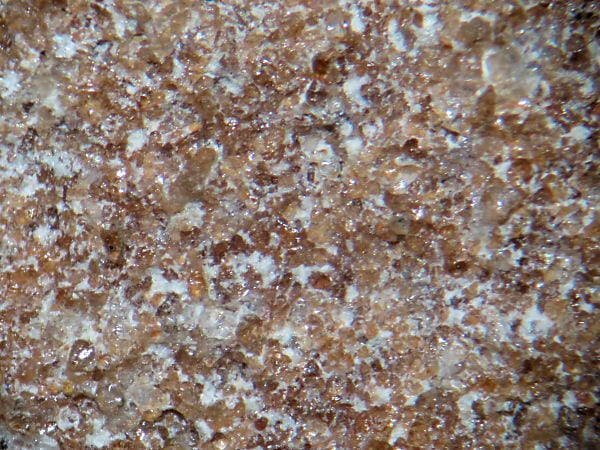

Sandstone

Sand grains are visible and some minerals can be identified with a hand lens or microscope. The grains are moderately well rounded (most grains roundish) and well sorted (grains all about the same size). In this case the grains are glassy clear quartz, colored reddish by a thin coating of hematite. The white material is clay between the grains. Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

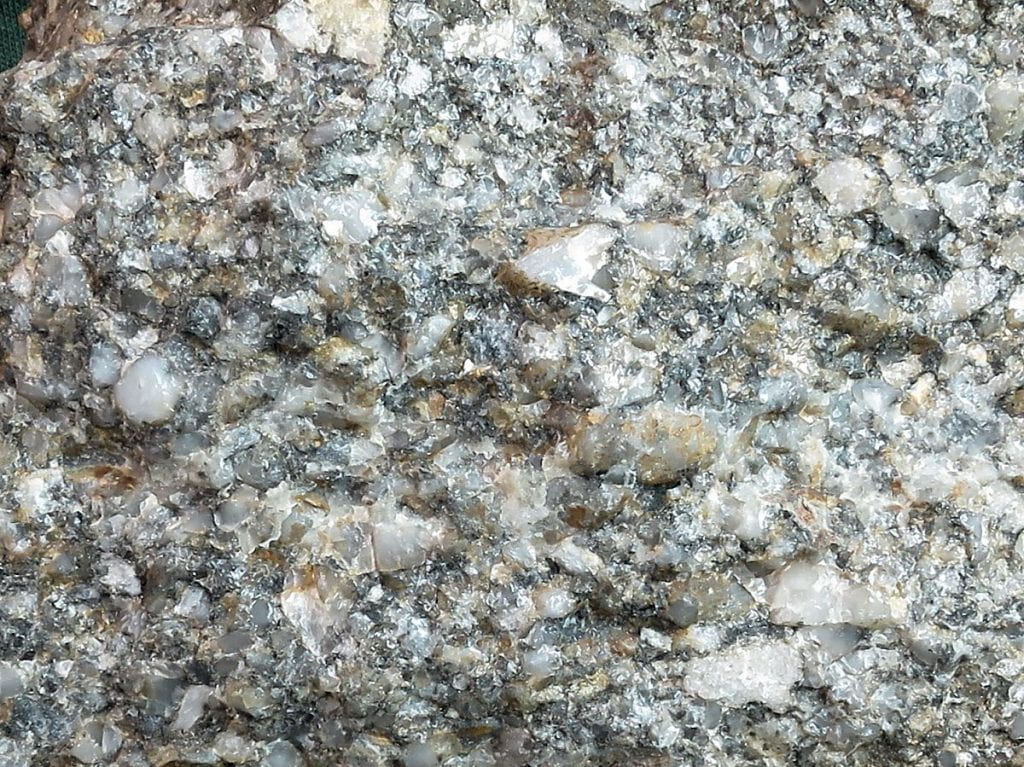

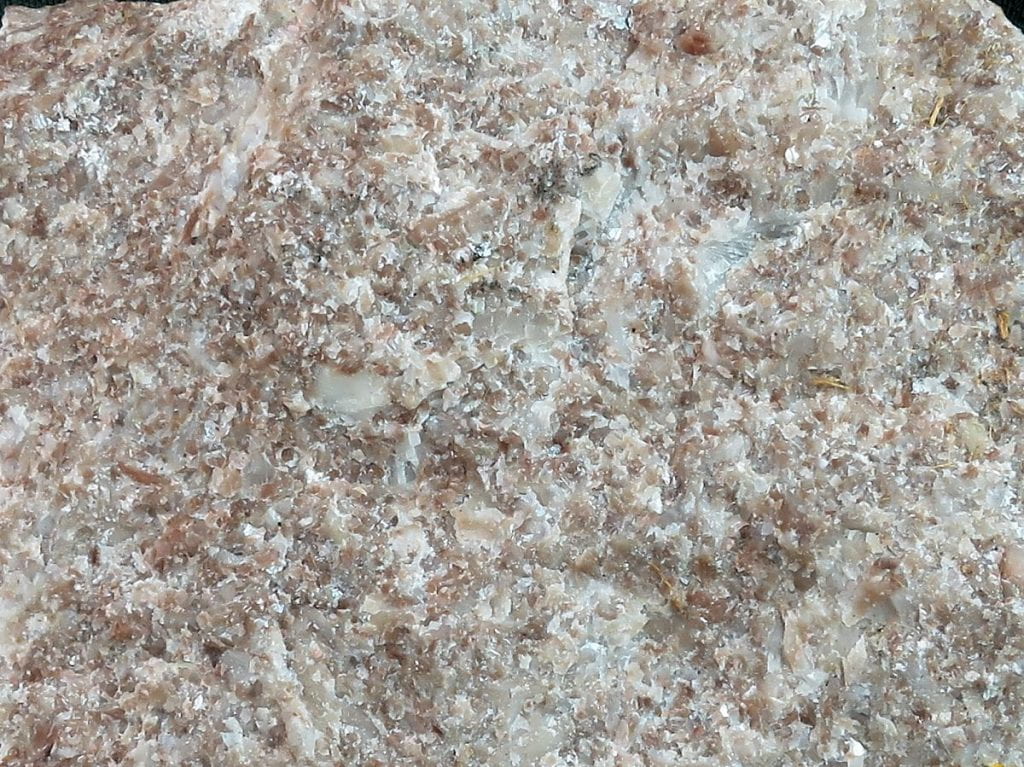

Arkose

This is a special type of sandstone having a lot of feldspar. Grains in arkose are usually angular (sharp corners on grains), indicating a short transport distance from the source area. Feldspar is a rather unstable mineral at Earth’s surface, so a lot of feldspar indicates a short transport distance, also. This sample happens to be poorly sorted (grains have a wide range of sizes). Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

Conglomerate

Conglomerates have most grains >2 mm, though almost always there are smaller grains between the big ones. These happen to be mostly made of quartz pebbles. Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

Conglomerate

Here are two more, much coarser than the one above. On the left, the largest grain is 10 cm across. Notice the toothy calcite crystals that grew in between the grains. On the right the largest grain is 5 cm across. This one was deposited by muddy water, so there is a lot of gray mud between the larger grains.

Limestones, example chemical sediment

Fine-grained

Here, most grains are too small to see with a hand lens. In thin section microfossils are visible. As with all limestone, the principal mineral is calcite. Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

Coarse-grained

This rock clearly has easily visible calcite crystals, and some fossils are identifiable. Notice the bivalve shells in the enlargement. Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

Oolitic

This limestone looks rather like a sandstone, because it’s made largely of sand-size calcite particles. Most of the particles have an outer shell of white, microcrystalline calcite that formed around them as they rolled around in tidal currents. They are common in tropical water carbonate banks. Right field of view is magnified about 10 times.

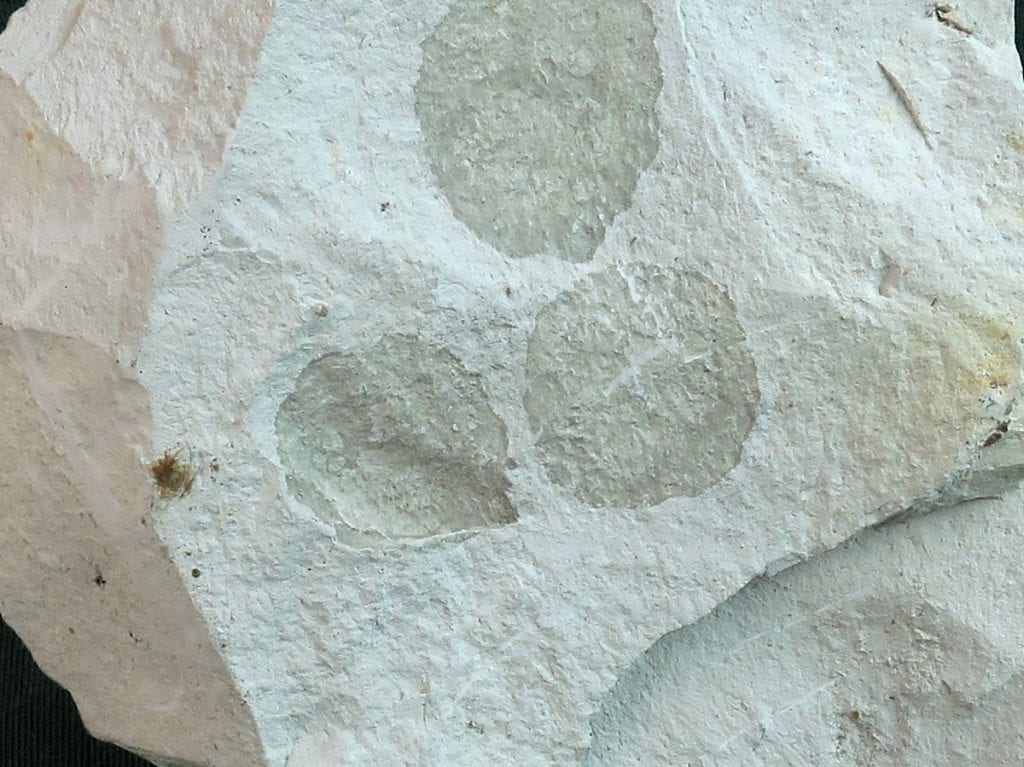

Fossil-rich

This limestone contains large numbers of bivalves, bryozoans, crinoid fragments, trilobite fragments, and many other remains of ancient oceanic life. The fossils are all encased in a gray calcite mud matrix, rather like what the fine-grained limestone is made of, above. Fossils can be found in just about any other kinds of sedimentary rocks, too.